You are here: Home / Part 6 New Truths of the Kingdom Aristocracy (Lessons #151–224) / Appendix A (#162–166) / Lesson 199 – Church History – The Modern Period, Eschatology

![]()

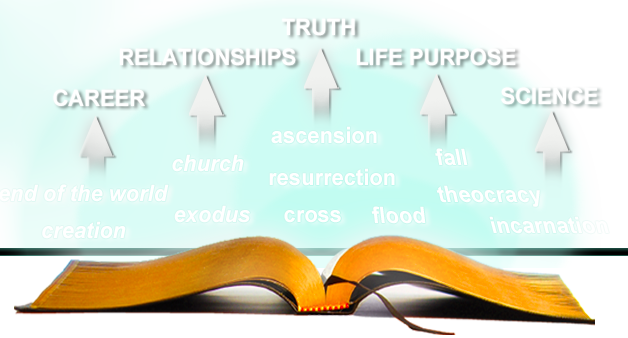

It's time to derive your worldview from the Bible

It's time to derive your worldview from the Bible

Rather than reading the Bible through the eyes of modern secularism, this provocative six-part course teaches you to read the Bible through its own eyes—as a record of God’s dealing with the human race. When you read it at this level, you will discover reasons to worship God in areas of life you probably never before associated with “religion.”

by Charles Clough

Church history. Grace is not a reward for obedience. The connection between the nature of the church and the nature of future things. Premillennialism, amillennialism, and postmillennialism. The church was premillennial for the first 300–400 years of its history. Matter is not inherently evil. Anti-Semitism. The Bible Conference Movement, the Scofield Bible and Fundamentalism. Your view of the nature of the church is intimately related to your eschatology. Questions and answers.

Series:Chapter 4 – The Historical Maturing of the Church

Duration:1 hr 32 mins 38 secs

© Charles A. Clough 2002

Charles A. Clough

Biblical Framework Series 1995–2003

Part 6: New Truths of the Kingdom Aristocracy

Chapter 4 – The Historical Maturing of the Church

Lesson 199 – Church History – The Modern Period, Eschatology

02 May 2002

Fellowship Chapel, Jarrettsville, MD

www.bibleframework.org

Tonight we’re going to finish the church history section. The next two or three times we meet we’re going to be on the Christian way of life in the Church Age, what’s unique about that versus the way believers lived in other dispensations. With that we’ll conclude and in the fall we’ll pick up with the end of the Church Age; that involves a whole other bucket of worms. Again, just to review, the Church Age, there is a sequence of the way the Holy Spirit has worked with the church. We saw in the foundational period that the Holy Spirit gave the Canon of Scripture and giving the Canon of Scripture solved the problem of who’s in authority. It solved the problem of what do we use as a standard of reference, and the standard is the Word of God. So we have the Canon given, though the Canon was not recognized in its entirety for centuries after that. At least the Canon existed at this time and the writings became available and were known.

Then we found that the next thing that was discussed was the Trinity and the Person of the Lord Jesus Christ. These are major topics and it shows you that if this is the way the Holy Spirit teaches, then we ought to learn from His lesson plan and what He starts with is revelation, authoritative revelation. So right with the Canon we already eliminate the supremacy of human reason and the supremacy of human experience. Neither reason nor experience is the final authority. It’s God’s Word and revelation that is the final authority. Once that question is resolved and we have the question of authority handled, then we go on to describe and to define and understand who God is, and particularly, who the Lord Jesus Christ is. We understand that because we go back to understand the content of revelation. It’s not how we feel, it’s not what we think the Trinity should be, what we think the Trinity shouldn’t be, what we think Jesus to be, what we don’t think Jesus should be; that’s not the issue. The issue is going back to the Canon; what does the Scripture say of the person of God and the person of the Lord Jesus Christ?

That was the first 400–500 years of the teaching of the Holy Spirit. Next we came down to the Middle Ages, and in the Middle Age period, for those centuries, the Holy Spirit was also teaching the church and in particular the issue was what was happening on the cross. We dealt with this, there’s two major ways of handling the cross of the Lord Jesus Christ. One is that something objective, something judicial, something forensic was done on the Cross. That’s one way; that is Anselm. Then the opposite of Anselm’s position on the Cross of Christ is that of Abelard, and Abelard’s point was that it’s not the objective work done on that Cross, but it’s the effect of the martyrdom of Jesus on my heart. So Anselm was subjective, it was what the Cross does for me, what the cross does for you or doesn’t do for you. It was to have an effect on the way people think, on our emotions, etc.

The point is that the cross does have an effect on our emotions, it does have a subjective effect, but think about it—it has it because of its objective truthfulness of what actually happened on the cross. So if what actually happened on the cross didn’t happen, and it was a tragic accident, a miscarriage of justice, a silly martyrdom of a good guy, then if you really took that position what subjective response is that going to have?

Then we came down to the Reformation period and that was how do we appropriate it, and the issue is we appropriate grace by faith and by faith alone, it cannot be appropriated by human merit. There are no human good works, God doesn’t deal His grace out drip-by-drip based on our obedience. If He did that we’d never get any grace; grace is not a reward for obedience. It is hard to say that because the Protestants immediately got in hot water with Catholic Europe over this issue because they said once you say this, then you’ve given people a license to sin. Well not really, not if you look at it from the standpoint of Scripture because God’s also a disciplinarian, so He handles that sort of a problem. But everybody is so afraid that as a result of this … the Reformation and the Roman Catholic issue about faith and faith alone appropriating God’s grace completely, what it boils down to is what is the motivation for the Christian life because that was the argument, that this thing would lead to bad things. If you really preached a gospel of the grace of God that is appropriated by faith and faith alone independently of human merit, then since you’ve excluded human merit as the basis for receiving the grace, you’ve taken away motivation.

But if you think about it backwards and say wait a minute, what is it that I’m receiving here. I’m receiving atonement for my sin; no matter how many good works I do, I still haven’t solved the problem of the atonement and my sin. It’s very interesting, I was reading the apologetic paper by a Pakistani Christian who witnesses a lot to Muslims, and in witnessing to Muslims you have a similar problem because Islam is built on works, literally, it’s a scale. If Allah thinks your scale is weighted on a good side, welcome aboard kind of thing. But this guy very cleverly points out, he said you know, isn’t it interesting, there’s not a country on earth, including the Muslim countries, where there’s a judicial system that works that way.

Think about it; what nation on earth has a law code that works like the following: person A is a good upstanding person in the community; person A one day kills his neighbor. Have you ever heard of a court saying because so and so did many good works in his life he’s absolved from murdering somebody? Do we ever have that justice working out? And he said you don’t see it in Pakistan, you don’t see it in Saudi Arabia, you don’t see it in Iraq, you don’t see it in Iran, you don’t see it in Egypt, you don’t see it in America, England, Germany, France. No country’s judicial system works on a balancing of good works against bad works. So then all of a sudden, now when we come to God, God’s supposed to operate by some sort of scheme that no country has, including the Muslim countries, including Roman Catholic countries. I thought it was an interesting point that he was driving at, showing the absurdity of salvation by works.

We forget what salvation is all about. Salvation isn’t about feeling good. Salvation isn’t a psychological pill. Salvation isn’t about how to go to a higher plain of life. Salvation is salvation from judgment against sin. Let’s get down to the judicial position. The problem is I need salvation because I am a sinner; I can’t save myself if I’ve committed a sin because the sin is on my record. I can’t get rid of that unless the judge does something; it’s out of my hands.

So that’s what came out of the Middle Ages. Last time we went on to what we’ll call the modern period of time and in this period we said that two things come up for emphasis and they’re still being worked on, and that is the nature of the church and the doctrine of future things. Those two go together and you can easily see why those two topics go together by thinking this way: we talk about the meaning of a word in a sentence by context. One of the rules of Bible study, when you read the Bible and you don’t know what a word means or there’s a nuance that you’re studying, there’s a set of rules that you use to find the meaning of that word. One is you look in the immediate sentence. If people would look in the immediate text of Ephesians 2:8–9 they’d understand that the gift can’t be faith there; the sentence isn’t constructed that way. The point is that you go into the immediate sentence, then you go into the immediate paragraph, then you go into the book because the book has an argument to it, does this meaning make sense in light of the overall meaning of the argument of book? Then you go into other works written by that same man. For example, if you’re studying Peter’s epistles, there are only three places in the Bible you can get Peter’s knowledge from, that’s 1 Peter, 2 Peter, and Mark, because Peter apparently was very involved with that particular gospel. Apart from Mark there’s only 1 and 2 Peter, so if you have a problem with 2 Peter 3:6 some place, the logical place to go is look at verse 6, go to 2 Peter 3, go to 2 Peter, go to 1 Peter, and maybe check what’s going on in Mark. That becomes your corpus and then after that if you can’t find something, now you go to Paul. But it’s the context.

History is like that, our lives are like that. The church has a place in history; it has a place in God’s plan, just like you and I have a place in history. What role do we play in history? The issue is what role does the church play in history? You can’t tell what role the church plays in history until you know what the plan of history is from beginning to end. That’s why these two topics, the nature of the church and future things are intimately tied together and your view of eschatology or future things will control what you think the church is all about. If you take one view of prophecy, we’ll go into that tonight, that’s what we’re going to work on, the connection between the nature of the church and the nature of future things. There is a logic that forces you, if you believe this way you’re going to believe that about the church; if you believe that way you’re going to believe this about the church. It’s nothing personal; it’s just that that’s the way the logic works out.

The church and future things: I said if you would look at the old notes, the three major views of future things. I want to start with a chart that goes back to the first century before Jesus because in the first century before Jesus there were a set of books being written called the Apocryphal writings. These are the books that are in the Catholic Bible that are not in the Protestant Bible. Several of these books take a certain position on future things. What’s important about these books is that they were trying to solve a problem that Judaism had. Let’s draw a time line from left to right. In Judaism the idea was going into the future we know that we would finally have an eternal blessing. In other words, God is going to separate good from evil and that’s going to be a permanent separation, it’s never going to mix up again and it’s going to go on forever. That was the general idea of history; history is going to end in eternal blessing, or eternal cursing. In other words, there will be a judgment at the end; there has to be to close the issue of the moral problem. If you don’t have judgment in your eschatology, you have not solved the problem of evil. People don’t like that, people don’t want to hear about judgment, but you can come back and say if you don’t like judgment in the future, you have no solution to the evil problem; those two things go together.

What they also had, they had various details, like here’s the judgment, they had the detail of resurrection, and they talked about kingdom conditions, and the triumph of Messiah in history, or the Messianic Kingdom. The question was, “How are these three related?”—that’s the question. How does the Messianic Kingdom get related to the eternal state, etc.? There are basically only some things possible. Here’s the time line, here’s eternity; we can say that the Kingdom is equal to eternity, it’s just another expression, they’re synonyms, so that once you have judgment you can go into the eternal Kingdom, so here’s how judgment goes and that makes the resurrection simultaneous with the judgment, and this Kingdom, the Millennial Kingdom is the same as the eternal state. That position comes over today as amillennialism, there is no Messianic Kingdom in this history, history goes on just the way it is now and then boom, it terminates with the return of Christ and we go into an eternal state. That view was prevalent, it wasn’t defined, it wasn’t developed, but that’s one logical possibility.

Another possibility was that there’s going to be a separation where the resurrection is going to be over here, ahead of the judgment, and in between those you’ll have the Messianic Kingdom. That was the view that was articulated, in fact before John wrote the book of Revelation, in the Apocryphal literature you read about a thousand year kingdom. That’s why we interpret the thousand years in Rev. 20 as literal, because that’s how people would have understood it. How do we know that people would understand it that way? Because that’s what was already written about in Apocryphal literature. So that’s one possibility, the Messianic Kingdom is between the resurrection and the judgment, and if that’s the case, that would correspond to what we would call premillennialism.

But there’s a third possibility and this one would have the time line, eternity, there’d be the judgment, there’d be the resurrection, this wasn’t true in the Jewish position so much as it came to be true in the Christian position and that is because the resurrection and ascension of Jesus introduced this thing called the church, that really what’s going on here is that the church is the fulfillment of the Messianic Kingdom. What in the Old Testament was thought to be the physical, material, political kingdom of a literal physical Messiah, literally ruling from literal Jerusalem in a literal way becomes spiritualized to be the church. So here’s the church and the church is now becoming the Kingdom. Let’s look at that for a moment because what that means is that the church spiritually fulfills the prophecies of the Kingdom. This position immediately introduces a new way of interpreting prophecy, i.e., the prophecy is different in how it’s fulfilled through the church than you would have thought if you had just been a reader of the Old Testament. There are some reasons why they say this.

By the way, the position with a Messianic Kingdom to be the church can also be amillennial in the sense that there’s no physical Kingdom. So in this view, for example, if the Millennial Kingdom is the church, you can bring the resurrection over against the judgment, terminate history, so it looks pretty much like the first one. However, there’s a variant on that, and that is because the church is the recipient of great and precious promises, there is a need for some triumphal termination to this history that we can say the church is going to increase and increase and increase and increase and increase and increase all the way until the Second Coming of Christ and the world will be Christianized. That optimism is called a postmillennial interpretation. What that means is that Jesus Christ, “post,” after, Jesus Christ comes back after the Millennial Kingdom, the Millennial Kingdom being the Church Age now.

There are three positions, amillennial, there is no Kingdom. As a variant of amillennialism we say that this is sort of a Kingdom now and it’s going to get better and better and better until Jesus comes back; that’s postmillennialism. Premillennialism separates the resurrection and the judgment and says that the Church Age is not the Kingdom. If you look at those three positions, just look at it logically, there’s only one of them that forcibly separates the church from Old Testament Kingdom imagery; it’s premillennialism. That’s the only one of the three because in this view the Church Age finishes, is done prior to the Kingdom coming, so the church doesn’t even participate in that Kingdom, there’s a relationship but the Church Age isn’t the Kingdom, the Kingdom is the Kingdom. In this view the church and the Kingdom are the same thing; the church is the Kingdom spiritualized.

So there are only three or four answers to this question of the future and one of the things that you want to train yourself to see through the way the Holy Spirit has taught the church is that on most theological questions there are not ten variants or ten possible answers. Most of the questions that have been dealt with in church history have only two or three answers possible, not ten, not eight, but probably only two or three. And you can spin your wheels, debate and argue, and whatever you want to do, there are only two or three answers to the big questions. It’s good news in the sense that at least you can master what the two or three variants are and learn to recognize them when you run across them.

We want to do that tonight, but I want to review a little about each one. I want to say a few things about premillennialism, the church and the Millennial Kingdom. In the period prior to Jesus and the New Testament, the premillennial idea of the resurrection being separated from the judgment, being part of this history, not eternity, not equated with eternity but part of this history, that tended to be the Jewish position going into the time of Jesus and the apostles. For example, R. H. Charles says of 1 Enoch, which is one of the books in the Apocrypha, “According to the universal expectation of the past the resurrection and the final judgment were to form the prelude to an everlasting Messianic Kingdom on earth but from this time forth” in the centuries immediately preceding Jesus and the apostles, “these events are relegated to its close, and the Messianic Kingdom is for the first time in literature conceived of being of temporary duration.” So this view was developing hundreds of years before the apostles and Jesus came onto the scene. It was part of the thinking that was going on in the Jewish community, trying to think through where Daniel led them, where Ezekiel led them, where the prophetic books led them. This is a result of thinking about this more deeply, particularly what was going on 200 years before Jesus and the apostles.

Think about it, because what is the rule that we’ve learned so far in church history about how does the Holy Spirit teach? He teaches by circumstantially pressuring people. He providentially works in the environment to put us in a situation where we are forced, literally forced to learn about Him. It’s true, sometimes we really get the light, it turns on and we learn the neat way, without being forced into something. But because we’re all a group of miserable fallen people, even though we’re being redeemed, most of the time we learn the hard way. Most of the time, we have to screw up 150 times before we finally get it. If you think about it, 200 years before the apostles and Jesus, what was the circumstantial pressure being put on the Jewish community? Conquest, they were being conquered. The one guy who is the precursor of the antichrist, he lived then. Do you know what his name was? Antiochus Epiphanies. He’s the guy that of all the men in history, we really should have biographies of Antiochus Epiphanies because it would give us a profile of what the antichrist is going to look like. He’s a nice guy, first of all—he wasn’t a scoundrel—he was a nice guy. His whole motivation was he wanted to amalgamate Jewish culture with Gentile culture, why can’t we all be one happy globe, one-worldism? See, antichrist. And he got really irritated like a lot of superficially good people, they’re great people until you cross them, and once you cross them, once you oppose them they turn into really nasty people. So a lot of good people can really become very, very nasty people once they’re crossed. Antiochus Epiphanies was one of those people and you can read the story in 1 Maccabees, what he did to the Jews when he discovered that they didn’t go along with his one-worldism and his one joint culture.

They revolted, they said no, we’re Jews, we’re not going to eat pork, and no our athletes are not going to go naked in a stadium and no we’re not going to do all the other things you say because we’re Jews and God’s Word says this. He came in hard on them. And then there was a big mess going on and finally the Romans conquered them. So here they are, a small Jewish community, always being conquered, always being oppressed. What do you suppose that does to you? It makes you want to think about where is history going, where is my hope? So in the centuries just prior to Jesus there was a lot of thinking going on about where is history going and during that they viewed, for reasons which we won’t go into, they started visualizing the Messianic Kingdom as a triumph when the Messiah will come, He will end Roman pressure, He will do away with the Antiochus Epiphanies and we will see victory and we will see His Kingdom come in this history, prior to eternity. That was their vision; that was their hope.

That sprung out of prior Christian centuries and it turned out for the first 100-200 years of church history on the other side of the cross, guess what the prevailing view was? Premillennialism. Listen to what Justin Martyr says: “But I and whoever are on all points right-minded Christians know that there will be a resurrection of the dead and a thousand years in Jerusalem, which will then be built, adorned, and enlarged as the prophets Ezekiel, Isaiah, and others declare … And, further, a certain man with us, named John, one of the Apostles of Christ, predicted by revelation that was made to him that those who believed in our Christ would spend a thousand years in Jerusalem, and thereafter the general, or so to speak briefly, the eternal resurrection and judgment of all men would likewise take place.” Does that sound like Justin Martyr might have read the book of Revelation?

That was the prevailing view. You say what happened to it, why did the church finally become amillennial? Christendom became amillennial after about 300–400 years. Premillennialism was shelved, it was suppressed, it was forgotten frankly, and the church became amillennial. There were various reasons why and again they’re circumstantial. Think about it, what happened 400-500 years after Christ? What was the big event that changed Christianity’s relationship to the Roman Empire? Constantine. Constantine became a Christian, at least nominally, and he said Christianity is going to be the official religion of the Roman Empire. When he did that what do you suppose that effect had on the persecuted position of the church? It relieved it. So there wasn’t a political depression, there was optimism in the air that at last the church had done something…well gee, maybe the church is the Kingdom after all.

Along with that was an increasing philosophic infatuation with Platonism, Augustine and some of these guys had philosophic presuppositions that they brought over from Greek philosophy, and one of the presuppositions that lead to this view was that matter is inherently evil; matter is inherently evil and good only triumphs in the spiritual things, not in the material things, the lust of the flesh, that sort of thing. What is the answer to that? If somebody comes up to you and says that matter is inherently evil, inherently evil, watch the word, inherently evil, what are you going to say to them? What’s your answer to that one? Are they right? Matter is inherently evil? What does that mean, inherently? It means that matter always has been evil. Was matter evil before the fall? Did God make matter evil? No. What about the resurrection of Jesus? Was that a material body of matter? He ate food, He said come here, touch Me, He wasn’t a ghost, He was matter in a resurrection body. That’s matter, is that evil? No. Oh, well then matter isn’t inherently evil is it? So that means that God can make good matter as well as tolerate this fallen thing we call our bodies and the fallen world around us. The Greeks, being good pagans, remember I showed the diagram, what is true of paganism over against Christianity as far as good and evil? The pagan view is that good and evil coexist forever and ever, there wasn’t a time when it started and there isn’t a time when it separates at the end. Greek philosophers thought that. Matter exists forever and ever, according to their position, and since good and evil exist forever and ever—guess what? Matter, therefore, must be evil inherently.

That was the presupposition brought over into the church by Augustine and other guys. So not only was it a politically optimistic age, it was Greek influenced. And then the third thing happened; the church did not want to be associated with Jews, the so-called Christ-killers as the church has often and sadly called the Jew, forgetting that Jesus was a Jew, Paul was a Jew, [and] John was a Jew. In fact, it seems to me that the New Testament was written mostly by Jews. It reminds me of the time when I had a friend witnessing to a Jewish businessman, they’d had several sessions of this and that, and the guy would get upset and argue with my friend. Finally he got frustrated one day and they were going at it, he had his Bible there and he was trying to show this guy something and the guy objected. So finally my friend in frustration said, do you know who wrote this, this isn’t a Gentile book, you Jews wrote it, so why am I wrong here, were these guys Jews or not. And it was very funny because the guy stopped because all of a sudden he realized hey, yeah, that’s our book.

I have a friend who’s a scientist and one day he was saying, we always kind of josh around together, and he said one day about the time pressure, gosh I wish we had more hours in our shift, a longer time to get stuff done. And I said well you ought to think of Joshua, that was a long day. And he has this Jewish accent, and he says, oh, that’s right, he was one of our boys. So they naturally think this way. The point was that the church was ashamed to be associated with Jews, the rise of anti-Semitism.

Amillennialism historically started in the fourth or fifth century, it totally dominated the church. Premillennialism was held by a few obscure people here and there, the few colonies in Switzerland somewhere in the mountains that hid out, but basically premillennialism died by AD 400–500. Everywhere amillennialism went it tends culturally toward … I won’t say it promotes anti-Semitism, but it allows anti-Semitism to develop, and you can see why.

On the bottom of page 103, I’m working with premillennialism there, “Premillennialism has exerted a strong influence upon American culture and its foreign policy.” I want to go through this because I want you to see that ideas have consequences, and then we’ll go back and deal with where premillennialism came from. But just to make it clear I want you to see in our world today why this idea of the Millennial Kingdom being the fulfillment of the Jewish nation of Israel, why that idea has affected American foreign policy. It really has, and it’s amazing to see this; in spite of the fact that people don’t really know why, it’s done this.

“Premillennialism has exerted a strong influence upon American culture and its foreign policy. By asserting a future for the nation Israel, premillennialism tends to be ‘Jew-friendly’ whereas postmillennialism and amillennialism historically permits anti-Semitism to rise in societies where those ideas dominate.” Think of where amillennialism dominates on a world map. Reformation countries were not necessarily pre-mil, they stimulated some of the premillennialism, but Germany is Catholic and Lutheran, both amillennial. Isn’t that an interesting observation? France was mostly Catholic before it became totally secular and therefore what was its eschatology? Amillennialism. Italy is solidly Roman Catholic, what’s its eschatology? Amillennialism. The Eastern Orthodox Church tends to be amillennial too. Russia, what’s the Christianity dominating Russia? Russian Orthodoxy and what’s its eschatology? Amillennial. So everywhere you see amillennialism what has been true about those countries and the programs against the Jews? They’ve all bred that, that’s what we’re talking about.

“Thus most of Europe, dominated as it is by amillennial viewpoint among institutions historically identified with the Christian faith.” I didn’t finish that sentence. “A few European exceptions have occurred. Balfour,” this is an interesting fact that Tommy Ice just mentioned to me. Do you know who Balfour was? He was the British foreign minister or adviser who arranged the treaty that set up the Palestinian state for Jews, not modern Israel, the thing that set up Israel in 1948, but back after World War I, in that era, the Palestinian mandate, which by the way in those days Palestinian meant Jewish person. In those days the Palestinian mandate effectively set up that area of the world as a Jewish colony, and Balfour was the Englishman that designed that policy. Historically it’s interesting that Balfour, the Englishman who approved the creation of the Jewish nation in Palestine was a premillennial Plymouth Brethren. The British foreign office has traditionally not been too friendly to Jews. In fact, one of the big problems they had in World War I was they got Lawrence of Arabia to go in and fight the Turks for the Ottoman Empire and fight them, get the Arabs on the side of Britain against the Ottoman Empire, and of course when he did that he had to promise something to the Arabs and here Lawrence of Arabia was promising the Arabs they could have this land. Then after the war the land is given to the Jews, boom. So right away you can see there is tension in there, how that whole thing was created.

But in any case, Balfour was one of the few Englishmen, and influential Englishmen that set that whole thing up, and he was, I think interestingly, a premillennial Plymouth Brethren. “In Germany during the rise of Hitler, premillennial brethren were the first Gentiles to recognize the significant evil in the Nazi agenda.” Footnote: “Hal Lindsey tells the story of the evangelical, premillennial Brethren” listen to who he was, he doesn’t mention the guy’s name because he heard about it from his son, “evangelical, premillennial Brethren, head of the German Army officers’ union in whose home the future leaders of the Third Reich (Hitler, Hess, Göring, Goebbels) met to try to secure his support to take control of the German government.” This is before Hitler got in power; this is in the early 1930s. They have this big meeting in this guy’s house, and they go to the guy’s house to have the meeting because he’s the head of the Germany Officer’s Union. Why do they go to his place? Who do you think they want to help the Nazis take over Germany? They want the allegiance of the military, so they go talk to this guy. This guy turns out to have been a Christian of evangelical brethren and he’s a premillennialist. Wrong guy, Hitler, you picked the wrong boy to talk to this time, not too smart. “… met to try to secure his support to take control of the German government. Realizing he could not persuade the Nazi leaders to give up their ‘Final Solution’ to their idea of a ‘Jewish problem’, he and his family at great financial loss fled to America” before World War II broke out.

I give those two incidents, Balfour and the Palestinian state and the head of the German army union—that was the union that controlled the military. Now we have two key actors in history that influenced history. It’s just illustrations of the role of premillennialists.

Back on page 103 you see that premillennialism has had a bad rep. You talk to Reformed, amillennial people, and they’ll remember these things. So if you’re identified as a premillennialist understand there is some bad baggage that has been historically associated with premillennialism and you will be called to task for this, even though you haven’t participated.

“Premillennialism had long been associated with Judaism and extremist cults. Not until after the Reformation did the renewed interest in Bible study lead to a resurrection of this view that had dominated the first few centuries. By the first half of the 19th century, Bible conferences began to emphasize the contrasts between Israel and the church observed through a literal interpretative approach to Scripture. It again” however “received bad press when the Adventist movement sought to ‘date-set’ the return of Christ only to be embarrassed by its non-occurrence in 1844.” That was when the Millerites got in New York. I don’t know what’s wrong, two places, New York state and California seem to generate all the religious kooks of the world; there’s something in the geography or something. But they got together in New York and got white sheets or something, all ready for the return of Jesus in 1844 and it never happened. That was a wonderful testimony to premillennialists. But a lesson was learned. You don’t date-set; there’s not any information in Scripture to date-set. We know the scheme of God’s prophecy but we don’t have any way of date-setting. And orthodox modern conservative premillennialism is never date-setting. When you read these books about the Rapture is going to happen next year, you can kiss it off because whoever is writing that kind of literature is not a historic premillennialist. They’re doing some bizarre thing with the text but it’s not the main line.

As Professor Hannah notes: “After the Civil War, a type of premillennialism emerged that eschewed date setting but insisted on the imminent return of Christ …. The teaching of the any-moment return of Christ in a secret Rapture accomplished the same purpose in that it created expectancy. This form of premillennialism became increasingly popular through the Bible conference movement….”

The Bible conference movement is something you ought to know about. The Bible conference movement was dating largely from 1865–1880, a fifteen-year period. It was right after the Civil War, after the country got back on its feet there were a series of Bible conferences in western Massachusetts and that same area, around Albany, etc.

The interesting thing about this Bible conference movement is that is where the theology of dispensations and premillennialism was actually preached [blank spot] … between 1865–1870 and 1880, it was a tremendous time of serious Christians seriously doing something. And the interesting thing was that this is before Palestine, they were already predicting the return of Israel on the basis of their premillennialism. If Jesus is going to come back and set up the Kingdom, and He’s going to do it with a temple in the land, guess what? Israel is going to have to come back in the land. So here these people are in 1880 looking forward to the return of the Jews to the land. When did Palestine start, it happened after World War I. Those were very key crucial points.

They were also key for another reason. The Bible conference movement led to the Scofield Bible because C. I. Scofield, the editor of the Scofield Bible was the guy who studied under the men who taught in that Bible conference movement; that’s the connection. What happened was, if you have a Scofield Bible you’ll notice the publisher; the publisher you would never have dreamed would have published the Scofield Bible, Oxford University Press. I remember Dr. Walvoord telling us at Dallas Seminary why that happened. That’s an interesting point of history.

Why do you suppose a world renowned publisher of the stature of Oxford University Press would print the fundamentalist Scofield Bible? Do you know why? Money. During the depression Oxford University Press was hurting, like a lot of companies, but they discovered something. No matter how poor people were they’d buy Bibles, and guess what the best-selling Bible was. So guess what Oxford University Press decided to print? The Scofield Bible. So it’s ironic that the Scofield Bible’s wide dissemination all over the world came about because of the effect of the depression on the publisher. So there were a number of things that were kind of interesting here, but the thing to remember about the Bible conference movement is it was the place where modern dispensational premillennialism was basically fixed. It was the place where the anticipation of the resurrected or revived state of Israel came to be voiced, and because the Scofield Bible came out of that and other conservative books the liberal assault on Christianity in America was retarded.

It wasn’t stopped but it was seriously retarded because people had the background from the teachers from that Bible conference movement. What would happen is people would go in the summer, they’d go to these Bible conferences, they’d get notes, they’d take notes back home, they’d start studying their Bibles like they’d never studied before, and then they’d hear some clown in the pulpit talk about well, we’re not sure whether the story of Noah is a fable or not. And they’d say wait a minute, whoa, what’s going on here.

So what you had is hundreds and hundreds of people, lay people in the major denominations raising their hand and saying wait a minute, what is it you’re teaching here, excuse me, I didn’t get that. So here these brilliant guys getting their doctorates from Germany, meshed in higher criticism of the Bible and liberalism that’d come sneaking into the seminaries and they’d start working on the poor guys, the country boys that were going to be pastors, and they’d sow seeds of doubt in these guys minds whether the Scripture was the Word of God and all the rest of it, it couldn’t have been Moses, Moses didn’t write it, JEDP wrote it and blah blah blah. And they’d go on and tear these guys faith apart and the poor kids would get in the pulpit, and gee, they wanted to do good things, so Christianity becomes a social movement.

The people that called it were the people who had been trained under the men in the Bible conference movement, and for that reason the liberal theologians have hated the Scofield Bible, they have hated Bible conferences, they have done everything they can to ridicule that. The word “fundamentalist” is a term today that is used pejoratively when actually do you know who started the word “fundamentalist?” It was a group of conservatives. By this time the fundamentalists, dispensational premillennialists that came out of the Bible conference movement and the conservative Reformed people got together and they put out a series of books. I have them at home, I finally found a set of these, you find them in used book stores or sometimes they republish them. If you ever see books advertised called The Fundamentals, it’s a historic set of books that you ought to get hold of because those books were written during about 1910.

What they were was some people started smelling a rat, these guys, these preachers, something’s going on, we don’t understand it but there’s liberalism coming in here, something doesn’t smell right. So they started saying we don’t even know whether our missionaries that we send out believe the Word of God, so what is it that we believe here. So The Fundamentals were the title of that book series and in the book they went through, here’s the fundamentals: the deity of Jesus, the authority of Scripture, the blood atonement, substitutionary atonement and all these things, and they said if people don’t hold to those fundamentals they’re not Christians. Phwoooo, oh, was that bigoted language. So the liberals come in and they say how dare you say that Joe isn’t a Christian because Joe doesn’t believe your fundamentals, that’s not very Christian of you to call him a pagan because he doesn’t believe… you know how it happens. But that’s where it got started, and that’s why the word fundamentalist has a certain onus to it because it comes out of the ridicule of the liberals because they didn’t like getting called. It was a nasty time in America, we think everything was sweetness and roses, it really wasn’t, it had a lot of problems.

But the big idea to learn here is that behind this movement, this wrenching debate that was going on, premillennialism played a vital role because it is the hardest of… of the three positions it’s the hardest one to reconcile with liberalism. Postmillennialism is easy, things are getting better and better, all we need is another social program, communism, fascism, or some other ism, all the modern isms fulfill and can be interpreted postmillennially. The Catholics in Latin America - what’s the big thing in the last 15–20 years in Latin America? Liberation theology; the Catholic Jesuits of all people, going into Latin America and preaching to the peasants and everybody else that the sin of the world, except by sin of the world they mean poverty, by the sin of the world they mean something else and those are results of sin but those aren’t sins. We’ve got to get rid of the sins of the world, so what we’re going to do is overthrow the dictators, overthrow them. And it’s true; they had weirdoes in the banana republics in Latin America. We’ve got to get rid of those guys, bring in the communists; they’ve got a good program. So now all of a sudden you have atheist communists joining with Roman Catholic priests to overthrow governments all over Latin America. How’d that get started? It wouldn’t have had the Catholic Church been premillennial. Amillennialism allows this kind of stuff. This is not a proof that it’s true, the only proof that you’ve got that it’s true is to go back to Scripture.

But in this section on history I want you to see that history is a laboratory where if you want to test what a believe leads to, you just know history and you can always test it. If this idea holds here, then this is the result. On page 102, we’ll talk about the other views. We’re going to talk about amillennialism and postmillennialism a little bit. “Reformed Protestantism unfortunately failed to correct Roman Catholic and Orthodox amillennialism. Amillennialism sees history as struggling along between good and evil, making no ethical progress, until the end of the world with the return of Jesus Christ. During the last two centuries unbelieving skeptics within organized Protestant circles have sought to redefine the purpose of the church,” see what happens, what did I say when we started? The nature of the church is intimately related to your view of future things. So, if the church really is the Kingdom, the church is involved in social society and politics. It’s politically activist, and it’s involved in social programs. It’s involved in economic programs because the Kingdom views … is that true or false, that the ultimate Kingdom has a political and social and economic aspect to it? Yes it does, think of the book of Deuteronomy.

So if the church is involved in the Kingdom, then the church is going to be involved in all those other areas. “This is why liberal clergy are often found in every movement for social change that happens to be viewed as ethically progressive. In Latin American even Roman Catholic theologians have embraced Marxist ‘liberation’ movements.”

“In Colonial America, some notable Puritans in their optimism over American’s opportunities turned to postmillennialism.” The Puritans were a mixed bag, they were premillennial Puritans, there were amillennial Puritans, and there were postmillennial Puritans. Don’t ever let anybody tell you that all Puritans were postmillennial. They were not. They had a lot of guys that were premil. In fact, in the notes I handed out years ago I list all the Puritans who were premil. In Colonial America they became postmil, then “Unitarian influences and later modernist teachers hijacked postmillennial visions and transformed then into vehicles of a ‘social gospel.’”

I once did a lot of research on this topic when I was in seminary and produced a paper, Walvoord said I should have published it, it’s been sitting on a shelf for 30–40 years, I never got around to it, but here’s a finding that I made. I went back through those years in our country and I started reading what the liberals were doing. And do you know, they came down, even though they would differ with each other, they came down in a vehement diatribe against premillennialism. Do you know why? They said if a person is a premil we can’t get them to believe in our programs. If a person is a premillennialist we can’t get them to go along with our programs! Of course, because we don’t believe we’re in the Kingdom.

“As Puritanism declined and Unitarianism increased,” see, that’s what’s happening in America, “As Puritanism declined Unitarianism increased,” and guess what the Unitarian vision of the future is? Postmillennialism. And what is the vehicle of salvation in Unitarianism? Ever been in a Unitarian Church, ever talked to a Unitarian; what’s the characteristic of them? Unitarians are always involved in education; they pride themselves on their intellect because education is the way of salvation for the future society. Once you master these ideas you can walk through these things and basically get oriented very quickly when you deal with people, because you just have to master these basic ideas.

Even Charles Hodge, by the way, who was a conservative Presbyterian at Princeton, he was a postmillennialist, so you had conservatives in the 19th century who were postmillennial. “In recent years postmillennialism has emerged again among conservatives” again, now they’re called “reconstructionists.” They’ve done some wonderful things. I’ve read a lot of the reconstructionist literature, and some of it, frankly, is wonderful. What they believe is you reconstruct every area of society on the Word of God. Well, it’s a nice motive to do that, the problem is if Christ doesn’t come back you’re dealing with sinful unregenerate people who don’t want society to be reconstructed on a Biblical basis. However, the positive side is that they have produced some wonderful stuff for Christians, at least, to think through these areas of economics and other places.

“Sever problems plague postmillennialism, however, viz. non-literal interpretation of prophetic passages of Scripture” why do you suppose that is? If the Millennial Kingdom was prophesied in Daniel and Ezekiel and Jeremiah and Isaiah and Nahum and Habakkuk, and Haggai, they’re all Jewish guys talking about what, the church or Israel? They’re talking about Israel; they’re talking about the Kingdom centering on Jerusalem. That’s Israel. So, this Kingdom is Jewish, it’s Semitic, it’s Jerusalem-centered - the church isn’t even in it. So to make the church get in it you’re going to have to change the hermeneutic. That’s why premillennialism is also characterized by what we call a literal method of interpreting the Scripture. That is, when I read a Kingdom passage, I interpret it literally.

For example, turn to Isaiah 2, here’s a good example. Here’s a passage that amillennialists have to make and bend and twist to make it fit the church. Pretend you’re a Jew, you’re sitting back in Israel and you’re reading Isaiah 2:1, “The word which Isaiah the son of Amoz saw concerning” who? “Judah,” that’s a Jewish tribe, there’s not anything about Gentiles here in verse 1. And what does it say, “and Jerusalem,” it’s not talking about Rome, Athens, Washington, D.C. “Now it will come about that [2] in the last days,” prophecy now, “in the last days, the mountain of the house of the LORD will be established as the chief of the mountains, and will be raised above the hills; and all the nations will stream to it.” Now that’s catastrophism, it’s talking about terrain modification in the nation so that the temple is going to be on the highest mountain on the earth during the Millennial Kingdom.

Verse 3, “And many peoples will come and say, ‘Come, let us go up to the mountain of the LORD to the house of the God of” who? Romans, Galatians, no, “the house of the God of Jacob; that He may teach us concerning His ways, and that we may walk in His paths, for the law will go forth from Zion,” not from the Vatican, “and the word of the LORD from Jerusalem.” Not from Rome, Frankfort or London. Verse 4, “And He will judge between the nations, and will render decisions for many peoples; and they will hammer their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks. Nation will not lift up sword against nation, and never again will they learn war.”

Everybody wants to skip to verse 4; in fact, I think verse 4 is on the UN building in New York City. But everybody leaves out verses 1, 2, and 3. We like verse 4, we don’t like verse 3. Why don’t you like verse 3? Because it says the Lord is going to judge, and it’s going be by means of His Word. So when you have the Kingdom established one of the signs if world peace. Does everybody like world peace? Sure everybody wants world peace.

If you’re screwed up in your eschatology you’ll be a sucker for all kinds of schemes, plots, programs and everything else. Premillennialism keeps you straight to the Scripture. You know that the conditions of verse 4 will not happen until the condition of verse 3 happens, until Jesus comes back. And until Jesus comes back there will be wars, isn’t that what He said, by the way, in Matt. 24, there will be wars and rumors of wars until what? Until I come back. So that means strong military. So one of the political implications of premillennialism is you have a strong national defense. People say well I’m kind of neutral on politics. Think logically, where do these positions lead to?

This is a quick overview. Next time we’ll get into the filling of the Holy Spirit and the unique things that are true of the Church Age.

Question asked: Clough replies: That’s a good question. The Scofield Bible was not at all firm on the six-day creation; they put the time in the gap there. I just finished an article that was printed in the Chafer Theological Seminary Journal last month in which I addressed that issue. What had happened was that when dispensational theology, i.e., the return to a literal interpretation of history started, right after the Reformation, and it was gradual, it’s been a gradual awareness; it’s not something that people sat in their room and thought it all through at once. The point was that even though potentially the literal method of interpretation would lead to modern creationism, it didn’t do so overnight. It only did so through the same teaching procedure that the Holy Spirit has used over the centuries, of going down blind alleys and finding it doesn’t work.

What had happened was that in the early 1830s and 1840s, keep in mind that prior to the Bible conference movement in 1860, about 1820, 1830 you had a movement in England that created the Plymouth Brethren, and central to that movement was a man by the name of Darby. And Darby was the guy who probably in church history put out a clear description of the difference between the church and Israel. He didn’t develop all the implications of that but he … he was an Anglican clergyman, always loved to point out the ecumenical background of these guys, there’s Presbyterians, Baptists, Anglicans, and everybody else in this because it was a church-wide revival of literal interpretation. Darby was an evangelist to Ireland, interestingly, Dublin, and he had experienced all kinds of problems witnessing to Catholic Irish. He was involved in that struggle and he was the one who finally put his finger on it, that the church was smearing the clarity between Israel and itself by not stating its destiny as distinct. So he was the guy who started that.

While that was happening in England, in New England here in our country, the first kind of waves of rethinking the history of Genesis 1 was going on. What had happened, if you go back to the science of it, right around the Reformation there were people who started in geology, for example, looking into the Noahic Flood, but it was a naïve belief in the Flood in that during the Middle Ages, prior to that time, people had seen fossils in the rocks and thought they were created in the rock. That was a prevalent belief in the Middle Ages. Then the Protestants started reading the Bible and they said wait a minute, you know, you go out in these rocks and you see these fossils, it’s all water laid, they’re sedimentary rocks. So they said that must be the flood.

Mixed in with all that there was a lot of new science … this was the age of science starting, which by the way was instigated a lot by Protestantism. Mixed in with that was a group of people who were not Christians, not regenerated, did not have a heart seeking for the Lord and to be bowing the knee to the authority of Scripture. And they went out and they, I believe, had a sinful mental attitude that they themselves did not even appreciate. By that what I mean is that when science began, modern science began, one of the early projects of modern science was to create a universal history, for the same reason that we just said how do you get perspective on yourself and the church if you don’t know the place of the church and yourself in the big plan? Science, modern science when it arose started what I call the universal history project which was a secularized attempt to reformat the plan of history and insulate man from divine intervention. There’s a motive. You can’t be naïve, we believe in the fallen nature. You cannot believe in the objectivity of science, I’m sorry. I’ve come out of science. Science is as influenced by sinful impulses as any other thing. And the sinful impulse manifested itself in an attempt to construct a view of history that would save man from any divine intervention. If you want a Scripture that shows you insights into that motive turn to 2 Peter 3:5-7.

What happened was that the geologists came in and they said oh, those rocks can’t be the flood of Noah, we believe in the flood of Noah and that Bible stuff, but you know, this is too much for Noah’s flood, and they had all these opposing questions. So quickly in geology it was all swept away. So by 1830–1840 Uniformitarianism came in, geology was witnessing to thousands and thousands of years of age, and the Bible couldn’t possibly be true. So there began in the 1800’s an attempt by the church to (quote) “come to terms” with science. And what the church failed to see, because they did not mine the Scriptures for all the data that God put in the Scriptures, the church prematurely, foolishly, concluded that this universal history project out there that the geologists had been working on was gospel truth, that it wasn’t an interpretation of reality, it was reality. And if this long ages [concept] was reality, and the Scripture also was reality, we’ve got to get these two together. So they desperately searched for ways of doing it that tried to keep the universal history project alive, with hundreds of thousands of years, it wasn’t millions and millions then, it was hundreds of thousands of years. They tried to keep that project going as truth and as reality, and then keep this Book going.

So one of the early attempts was you’ve got to get disposed of time. Where do you dispose of time and that came up with this Genesis 1:1–Genesis 1:2 gap. So when Scofield, a hundred years later, think of the time, a hundred years later Scofield comes out with his Bible, things haven’t changed, it’s the only tool the church had thought about to try and reconcile the universal history project with the Bible. The problem is, by the time Scofield came out with his Bible the universal history project had progressed far on down the line, it was talking not about 200,000 year histories, 500,000 year histories, by 1930 they were talking about millions of years of history. So the church in the 19th century up to the time of the Scofield Bible, they tried every way that you can imagine to harmonize.

The first one was the gap view, then people didn’t like that so they said well, gosh, there was development, because by this time it wasn’t the geologists involved in the universal history project, but also who else joined them with Darwin? The biologists. So now not only were the geologists talking about long time, now the biologists were talking about you need a long time to transform from primitive to advanced life forms. So now there had to be a development going on. Well, how do you fit that in with the gap view? So by 1840–1850 now we come out and say…

Dr. Hannah, the guy I quoted in the notes, the historian, he did a paper on this, it was published back, I guess in the late 70s, where Dr. Hannah went back and the took the theological journals, like Bibliotheca Sacra and he went all the way back to 1830 and he traced it from 1830–1880, and looked at every single article that dealt with Genesis and creation. And he traced over those 40–50 years, first it was the gap view, then the biologists came in and so they had to do time so the way they handled time was the day-age view. Now the days are ages. Then there came in, by the end of the period of 1880–1890 evolution had so come in, and Darwin had written in 1865–1870, right after the Civil War, Darwin had already written Origin of the Species, it was circulating all through England, it came to America and at this point the conservatives, most of the Reformed conservative camp that were represented in this journal said well, we don’t believe in the gap, gap doesn’t solve our problem, day-ages somehow it’s there but we just have to accommodate the facts of modern science.

That’s the way it was left up until 1960, largely. Prior to that the only people that had, ironically, spoken out was a cult about creation and that we have to admit that the Seventh Day Adventists were the ones who said no, we don’t believe in the gap, we believe in a literal Genesis. That’s interesting because the Seventh Day Adventists of all the cults is closest to orthodoxy. They were the ones who had their literal interpretation that led, unfortunately to the dating schemes of 1844, but they were also the people who in their schools honored a literal Genesis. And they tried to produce a few scholars that tried to deal with reconciling the Bible but they always had enough respect for the text that they, unlike the rest of the church including the evangelicals, they said you know, there are certain limits, you can’t just go into the text and make the text say anything you want it to say. And they held the line, but they never produced any people who wrote, who would really put pain into the liberals.

In 1960 two men decided they were going to do it, Whitcomb and Morris. Whitcomb was an Old Testament scholar, graduated from Princeton, had the academics; Henry Morris was the head, he taught hydraulic engineering, of all things, of all the engineering things that deal geology, he’s the guy that wrote the textbook on hydraulics, that there’s water deposition, etc. He was a godly Christian and so was John Whitcomb. They got together and said we’re going to tackle this thing. And they were both dispensational literal interpreters of the Bible, and what they did was breath-taking. I wrote my thesis at Dallas Seminary on what they did. I surveyed every single book review that was ever written on their book, The Genesis Flood. I had responses from evangelical scientists like this: If I wore the blinders on my mind that Henry Morris wears on his I would deny my faith, a Christian faculty member. Another one wrote in a public magazine when he was reviewing the book: well, geologists have spent two or three hundred years building the science of historical geology and now Whitcomb and Morris come along with a family Bible and try to make all geologists drive trucks now because their science is so bad. Sarcastic, nasty reviews.

But you see, what happened was that Whitcomb and Morris did something that no one else in church history had ever done before. That’s why it was a significant book. What they said was if you go back 300 years, all the way back to the Reformation, and you look, who has been successful in reconciling this book with the universal history project? No one! Every device and scheme of trying to reconcile them has failed. The gap theory failed. Why did the gap theory fail? Do you know why the gap theory failed? Because you still have literal days. God’s still creating, whether it’s recreating or not, you’ve got a miraculous thing going on. Now that you’ve put all the geology in time spins behind Genesis 1:2, now where’s the geological evidence of the universal flood? There are all kinds of internal problems. If you take the days to be ages, now you’ve got a sequence problem. The days are out of sequence. The days, if they’re ages, do not fit the evolutionary time frame. What evolutionary time frame postulates is that plants came into existence and after that the stars. The days are out of sequence. And people know this, it’s not me. It just never worked, nothing ever worked.

So Whitcomb and Morris came up and said hey, wait a minute, here’s why it’s never worked; you guys are trying to reconcile the Scriptures with the wrong thing. You guys are taking this book that’s been created by unbelievers for 300 years, called the universal history project, and you’re taking this not as an interpretation of the facts, you’re taking it as fact. The universal history project is true, it’s objectively proven to be true, and you’re trying to make these two come together and you can’t get them together.

So what Whitcomb and Morris simply was this is wrong. And guess what guys; we’re going to start all over from scratch. That thing, that whole universally history project got off to a wrong start. Your radioactive dates, there is systematic error in them somewhere, we don’t know where it is, but the error has to be in there. The issue of the speed of light, there’s a hidden fallacy in that too. In geology they were able to show fallacies because Morris knew his hydraulics, he went out and he took pictures of over thrusts where you have old rock, supposedly, old rock on top of younger rock, i.e., rock that has been dated because of the fossils in it, as old, it’s got primitive fossils, and it’s lying on top of new rock. The traditional evolutionary explanation for that is this is a sheer zone, where the rocks got sheered and went like this. Whitcomb and Morris did and a couple of his allies, they went out and they found where the interface along the rock was like this, and they said if you had a sheer zone you wouldn’t have tape on it, that rock was deposited that way. So it’s not that old rock, it’s the new rock. So you’ve guys got a problem somewhere.

They raised so many problems in their book, including the fact—and the embarrassing fact—that radioactive dating sometimes yield negative ages. There’s a cute one for you. Live mollusks date at three million years old. Huh! It’s alive, how can it be three million years old? You have this stuff that goes on and they raised all the dirty linen that was buried in the universal history project. And I’ll tell you what, boy were they vilified, even evangelical Christians vilified them because the evangelical Christians that came against them were embarrassed because they were Christian people involved in the establishment that was involved in the universal history project. These guys have their salaries paid by research grants that are trying to support the universal history project. So they got ticked off, plus the fact I think they were spiritually embarrassed that here’s a brave man, a godly man, who finally stood up and said no, you’re wrong, and I stand for the authority of Scripture. These guys had compromised all their professional life, and once you start down the road of compromise you’re really faked out. So they got caught and they didn’t like it.

Ever since then there’s been a divergence. Right now, the last 8 years, we’ve got a guy going around, he’s on the Dobson show, a bunch of others, called Hugh Ross and he’s supposed to be some Christian physicist and he believes in long ages and all the rest of it, and we’re all screwed up, the Bible isn’t the way it really appears to be. For twenty centuries Christians have read the Bible seven literal days but now we suddenly decide the days aren’t literal. Come on!

Anyway, if you look at guys like Hugh Ross that are impressing Bill Bright, James Dobson, and others, if you look at him and you look at his tactics and his approach, it’s exactly what happened in the 19th century. I told Tommy Ice we ought to write an article about Hugh Ross, he’s in the wrong century, he ought to go back to the 19th century and go all over again, because he’s using the same arguments, day-age, maybe it’s a framework hypothesis, that’s the new one, they’re literal days but it’s just the literary structure God used to describe millions of years.

The point is—an excellent question that was raised because it shows that in church history things don’t jell all at once. There’s a gradual process of growing awareness and creationism started in 1960, really the modern movement, it’s a new movement. That’s why it’s phenomenal as to what it has done so far, with very, very little resources. You think of what the universal history project did, for two or three hundred years they’ve gone out and gone all over the surface of the earth and under the earth, taking pictures, taking data, analyzing the data within that frame of reference. Now you talk about coming from behind, you know, we’re coming from two or three hundred years behind, we’re not going to take all that data and re-synthesize it over night, it’s going to take years, centuries if the Lord tarries, and maybe He won’t and then we’ll be doing that in the Millennial Kingdom. So what!

But there’s a gradual awareness; one generation of Christians never get it all together. They make advances, they make more understanding here, more understanding here, but no one generation is going to have it all, and we don’t. We just have to understand where we are in the progress of the Holy Spirit’s teaching the church. And in our day the issue is the nature of the church and future things. Maybe there’s something else to expand on before Jesus comes back, I don’t know, but that’s obviously what’s happened the last 200 years. And the result of that is when the eschatology gets fixed, gradually it’s getting fixed, all the other answers are going away, and as eschatology jells, guess what? That is the frame of reference for the new universal history. The universal history shouldn’t be that, it should be this; it’s the Word of God that gives the framework.

So that’s why in our day I believe firmly that eschatology is the issue. It’s not just a peripheral thing to be treated lightly, oh well, we don’t bother with eschatology. I think we have to bother with eschatology because every adverse movement to the church is an eschatological movement. The universal history project is an eschatology; it’s a fake false pagan-based eschatology. Communism was an eschatological political system; fascism was an eschatological political system.

Islam, the fundamental Islam, has a political agenda and what is it? To conquer the world, hence to make every member of the human race submit and bow to Allah, which means bow to the mullahs. And that’s an eschatological vision of where history should be going and their place in it. The suicide bombers—they have an eschatology. Come on, what is it, it’s on the radio and television all the time. What do they believe is going to happen to them, if they kill somebody and blow somebody up? They get to fornicate with 72 virgins for the rest of eternity. So, that’s an eschatology, isn’t it? Every movement that you think of that we’re faced with in the last hundred years has been an eschatological movement. So what do you think the Holy Spirit is emphasizing. Come on church, get your eschatology together.

Question asked or statement made: Clough replies: Yes, and I’ll tell you what, it’s very strong in Maryland in Reformed circles. What’s interesting about it is that you have the church supposedly takes over the blessings of Israel; what about the cursings? What about the cursings, how come the church doesn’t take over the cursings of Israel. Just as an example, Tommy Ice was at a debate, doing a debate that he’s given several places around the nation, with preterism. Preterism follows out from postmillennialism. Basically what preterism is is the belief that Jesus has already come back, and that AD 70 was the fulfillment of all those things. This is all through Maryland now. The idea there is preterism; what are the preterists doing? The preterists are spiritualizing the language of revelation. Stars aren’t falling from heaven in AD 70, so the stars that fall from heaven have to be something other than literal stars falling from heaven. So now we’re spiritualizing Matthew and Revelation.

There are answers to that. Basically the answer is that Jesus and John are using language of Isaiah, Hosea, and Jeremiah. Now where did Isaiah, Hosea, Jeremiah, and Daniel get their language from? Israel’s history. What do you find in Israel’s history in Egypt? The sun turned to darkness. You have the plagues, you have the pestilence. Was that spiritual? Was that the Egyptian army in the Exodus? No, it was physical catastrophic events. And the prophets have taken over that language of physical catastrophism to phrase their prophecies of the future. The preterists know this so guess what, now they’ve started a website in which they’re denying and calling all Reformed people back to a non-literal view of Genesis. And they’ve got to because they’re holding to a non-literal view in Revelation and how you handle Revelation is related to how you handle Genesis. So the logic of their position, this is the way God works in history, you purge out stupidity, and stupidity can mask itself for a while, but finally it starts to part and you begin to say wait a minute, where is this road leading to. That process takes decades to… [message ends abruptly]