You are here: Home / Part 2 Buried Truths of Origins (Lessons #1–33) / Part 2 Introduction (#1) / Lesson 132 – Biblical Thinking: Dealing with Modern Pagan Worldviews

![]()

It's time to derive your worldview from the Bible

It's time to derive your worldview from the Bible

Rather than reading the Bible through the eyes of modern secularism, this provocative six-part course teaches you to read the Bible through its own eyes—as a record of God’s dealing with the human race. When you read it at this level, you will discover reasons to worship God in areas of life you probably never before associated with “religion.”

by Charles Clough

Biblical faith is an historic faith. You can’t have doctrinal truths without historical integrity. The dilemma and limitations of the empirical approach. In every area of life, start with the Word of God. Questions and answers.

Note:The text for the “Is the Bible True?” article is included at the bottom of the transcript.

Series:Chapter 4 – The Death of the King

Duration:1 hr 23 mins 52 secs

© Charles A. Clough 1999

Charles A. Clough

Biblical Framework Series 1995–2003

Part 5: Confrontation with the King

Chapter 4: The Death of the King

Lesson 132 – Biblical Thinking: Dealing with Modern Pagan Worldviews

04 Nov 1999

Fellowship Chapel, Jarrettsville, MD

www.bibleframework.org

We’re stopping our forward progress through the Christology to deal with an article that appeared in U.S. News and World Report, the October 25th issue, and I’d like to read some sections of this article because this would normally be viewed, and by most readers it’s not a virally anti-Christian article, in fact some people would argue that it is friendly, it’s a friendly article. The title feature story on the front page, “Is the Bible True?”, and an artistic rendition of Adam and Eve (see the text from this article at the end of this transcript). I want to take this time to go through this and I hope that as we go through this you’ll see a reason why I set up this framework the way I did, and why I really believe this is a way of approaching Scripture that’s quite important for us, particularly in the 20th century and now the 21st century.

Feel free to interact because I’m going to throw out questions for responses. In some of this there won’t be (quote) “the right answer” but we’re dealing with an approach. This article would represent probably on the spectrum from love to hate, it represents a somewhat lukewarm view of Christianity. This would be the kind of thing that I believe most people in the street would readily accept. I think it’s important that we interact with it, and begin to draw upon some of the elements that we’ve been studying in the Framework series. This surely, the environment in which we live, if we were to witness for Christ, if we were going to discuss the gospel, if we’re going to stand fast in our personal faith, unless we’re obscurants, we have to deal with this sort of thing.

I’m going to start off noting a few things and hopefully, not that I have all the answers as far as methodology goes here, but I’d like maybe to, if you take notes, just notice some of the things, how we get at this kind of thing, how we respond to it, we don’t just sit there and read it and take it in and say I believe that or I don’t believe that. It’s not that simple, we want to interact with it.

The first thing, I’ll read the front page of it. Here’s the title, and let’s just look at the title a moment and let’s think about what we’ve been talking about in the Framework series. The title is: “Is the Bible True?” It has a number of subtitles that the editors have put onto the article, but it’s a typical question and I want to look at this. “Is the Bible True?” Then there’s a subtitle under it, “New discoveries offer surprising support for key moments in the Scriptures.” Then you open the magazine and you turn over to the article, and there’s another little subtitle there, “Is the Bible True?” main title repeated, this time the subtitle says “Extraordinary insights from archeology and history.”

When we started this Framework, remember that I kept saying what about questions? What did we say about questions? You don’t buy into the question without first thinking whether the question is already loaded. The classic being when someone says how many times last week did you beat your wife. It’s a loaded question; you can’t get out of the question because the question has already set up the discussion. One of the things that you want to notice here about this is that there’s a lot of stuff right here in this question. It looks like a very innocent question, and a lot of people mean it innocently. It’s not that there’s a big line of deceit here going on, it’s just that we want to be careful when we get into this kind of a thing, because remember the world system is a playground of Satan, and he’s very brilliant and can ask some very brilliant questions.

What do you notice about this question? Anybody catch something about this question? [Someone replies: that the Bible might be false]. Clough: Okay, one of the obvious things is that the Bible may or may not be true, and we’re going to have to find out whether it is. That seems to imply that we have some sort of a neutrality going on here that we’re all sitting on neutral ground and now we are going to decide whether or not the Bible is true. Isn’t that what the question is?

What event in Scripture that we’ve studied in the Framework does this remind you of? The Garden of Eden, so turn there. Turn to Genesis 3, and please don’t misinterpret the spirit in which some of this criticism is offered. I’m not here to smash somebody that asked that question because people can genuinely ask that question and in a loving gracious way, we just have to be sure that we don’t buy into things and allow them to buy into things. It’s like you’re on a lifeboat and somebody’s drowning and you may have compassion and concern for them, but in the act of trying to save them you don’t want to destroy yourself because if you did you’d go in the water and now we’ve got two people drowning instead of one. So that’s the picture you have here. So we’re not trying to be nasty, we’re not trying to be picky, but we are trying to be discerning.

Let’s look at the text in Genesis 3 when Satan comes to Eve. Verse 1, “… And he said to the woman, ‘Indeed, has God said, “You shall not eat from any tree of the garden?” ’ “ Of course we know this discourse goes on. He approaches with a question. Questions are very powerful. They’re good teaching tools; they’re in some sense less confrontational than an affirmative sentence. To ask a question you’re deferring to someone else, so in one way you’re complementing their ability to respond to you, you’re beginning a conversation. But in this case, Satan is saying, “Has God said you shall not eat of the tree?” and the woman sort of slightly misquotes the thing, verses 2-3, and she concludes in verse 3 with the statement, what did God tell her. If you’re going to eat, what’s going to happen? You’re going to die.

In verse 4, Satan says “You surely shall not die!” So here’s Eve, who now is in the middle of two propositions. God says you will die. Satan says you will not die. And Eve is going to determine which one is true. Eve is going to undertake an investigation. Eve is going to say to herself that she has within her power the capacity to decide what is true and what is false. What has implicitly occurred right away in this picture? Already something is wrong. We’ve put the two statements as though both those propositions, you will die, you will not die, are equal and opposite. But in fact, are they? Is it true or is it not true? This is the proposition that comes from God; this is the proposition that comes from the creature. Can those two propositions be rightly equated as to level of authority? No they can’t. But this comes so fast and this is how Satan trips us up in our minds, because 90% of the Christian battle is right up here, it’s not with the externals, it’s right here. When we get off track, and Satan has a thousand ways of getting us all out of fellowship, off track, screwed up, and one of his favorites is to mask the issue and push us over here and get us… it’s like the magician, a good magician is a slight of hand artist; they always get your attention in the wrong place while they’re doing something else. That’s exactly how Satan operates. We just don’t see the thing, we get deflected, we get distracted, and we’re looking at the wrong place.

See, Eve was concerned with the question, the dialog, and immediately she starts rolling on as though these two statements are equal and opposite. But the moment she did that, what was she doing for herself, as far as authority goes? She relegates to herself the authority to decide whether God is correct or He isn’t, whether Satan is correct or he isn’t. So right now, in this position, Eve has it set up so that man determines what is true and what is false. Keep that in mind, we’re going to get into some problems with that, because this is a classic error that man makes.

In the case of this article that we’re studying, the object of discussion is the Bible. And we’ve said that no matter what the topic is, whether it’s the Bible, marriage, work, politics or what, we all come to an issue and envelop that issue with a frame of reference, with a framework of thinking. If, for example, we throw out evidence, we’ve used this illustration before and we’ll use it again in our series when we deal with the resurrection of Christ, people like to say for example, oh, look at the evidences for the resurrection of Jesus.

A clever unbeliever could accept those evidences for the resurrection of Jesus and still reject the faith in the gospel. How could he do that? By simply saying oh, gee, Jesus must have risen from the dead, strange things happen in the universe, this is just one of them, this is a contingent universe, you know. What’s happened now? All your evidences that were piled on to make that point that Jesus rose from the dead suddenly it’s like somebody pulled the switch and all your work went to nothing, it just went swoop right into a big hopper, because it was absorbed and it was outmaneuvered.

What we call this is strategic envelopment. There’s a game being played here, all the time, going on in our heads. No matter what the issue is, no matter what the pressure point is, no matter what the discussion is, the issue is, who’s doing the strategic envelopment. Is the Scripture, is God’s Word, able to come around this and interpret this situation, or unconsciously half-heartedly are we passive spiritually and we’re allowing the world system to come in here and interpret this whole issue in this larger apostate unbelieving frame of reference?

Right from the start when we read the article, we say “Is the Bible True?” and underneath there is the sub-statement, right underneath the title here, it says “New discoveries offer surprising support for key moments in the Scriptures.” So the methodology of the question, how are we going to answer this? We’re going to answer the question whether the Bible is true by new discoveries. In other words, we’re going to go out into the world, we’re going to do experiments. We’re going to walk the lengths and the heights and the depths of the universe and see if we can spot evidence whether or not the Scriptures are true. Just like Eve, if I eat of the tree, then I can tell which statement is correct. But the dilemma is if I ate of the tree, what have I already done? I’ve already disobeyed God.

So God deliberately set up the thing in the garden so there was only one way for Eve … could Eve rightfully have solved the dilemma here without disobeying God? Yes she could have. How would she have done that? She would have had to obey God. Then you say yea but then she couldn’t ever tell what would happen if she disobeyed God. That’s right, she couldn’t tell what would have happened, she would have to take it by faith, the fact that if she had disobeyed God what would happen? She’d die. How was she doing that? She was taking it by faith. When we take it by faith, whose authority are we automatically thereby accepting? The author of Scripture. So we’re back to an authority issue. Whose authority are we going to have? Eve took it out of God’s hands and decided she would be the final arbiter of truth and reason.

So much for that, on the inside we have “Is the Bible True?” and we have “Extraordinary insights from archeology and history.” So now already the authors have set us up because they’re going to tell us, and they’re announcing it right here, the method they’re going to use to answer the question. The method is going to be discoveries, archeology, and history. We haven’t even read the article yet, and this is the kind of things you want to learn to do. You don’t have to read 800 pages here, just look at the big idea. If it’s a good article and a good writer, this is why you really want to read good… if you ever read unbelievers read good ones that are literary people that write well. People that write for Time and Newsweek are good writers. They wouldn’t be on the staff if they weren’t. Here we have them coming in and they’re saying to us that we’re going to answer the question, “Is the Bible True?” and we’re going to answer it by means of discoveries, in particular we’re going to look at history, and archeology, that’s the method. Think of what I just said about strategic envelopment. What’s going on here? Here’s the Bible, and what is it being enveloped by? History and archeology. You say what’s wrong with history and archeology? If history and archeology have developed by themselves independently of Scripture, now what are we working with.

Let me give you an example. You’ll see this in the article. In the article they’re going to say gee, you know we thought that David was a mythological figure. Why would you think that David was a mythological figure? It’s in the Bible. Yea, but why, if it’s in the Bible, are you considering it a mythological figure? Why do you a priori say anything in the Bible … well, that’s the question, the question is whether the Bible is true or not, we’ve got to go outside of the Bible to look at the Bible. But if we go outside of the Bible and we rely upon the history and an archeological frame of reference that itself has from the very start rejected the authority of Scripture, then how are we going to learn about the Bible’s authority by looking at an anti-authority frame of reference?

Let me go through and I’ll read some of the sentences to you so you can catch the flavor of this article. Like I said, you can look at this article and nine people out of ten that read this, even believers, will classify this article as a friendly article. And compared to a lot of the virulent stuff you read, this guy is at least gracious, let me put it that way. The article starts out in a nice way, it says: “The workday was nearly over for the team of archeologists excavating the ruins of the ancient Israelite city of Dan in upper Galilee. Led by Avraham Biran of Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem, the group had been toiling since early morning, sifting debris in a stone-paved plaza outside what had been the city’s main gate.”

“Now the fierce afternoon sun was turning the stone works into a reflective oven. Gila Cook, the team’s surveyor, was about to take a break when something caught her eye—an unusual shadow in the portion of a recently exposed wall along the east side of the plaza. Moving closer, she discovered a flattened, basalt stone protruding from the ground with what appeared to be Aramaic letters etched into its smooth surface. She called Biran over for a look. As the veteran archeologist knelt to examine the stone, his eyes widened. ‘Oh, my God,’ he exclaimed. We have an inscription?’”

“In an instant, Biran knew that they had stumbled upon a rare treasure. The basalt stone was quickly identified as part of a shattered monument, or stele, from the ninth century B.C., apparently commemorating a military victory of the king of Damascus over two ancient enemies. One foe the fragment identified as the [quote] ‘king of Israel.’ The other was [quote] ‘the House of David.’ The reference to David was a historical bombshell. Never before that the familiar name of Judah’s ancient warrior king, a central figure of the Hebrew Bible and, according to Christian Scripture, an ancestor of Jesus, been found in the records of antiquity outside the pages of the Bible. Skeptics had long seized upon that fact to argue that David was a mere legend, invented by Hebrew scribes during, or shortly after, Israel’s Babylonian exile, roughly 500 years before the birth of Christ.”

Now listen to this next sentence and see what it says. “Now, at last, there was material evidence: an inscription, written not by Hebrew scribes but by an enemy of the Israelites a little more than a century after David’s presumptive lifetime. It seemed to be a clear corroboration of the existence of King David’s dynasty and, by implication, of David himself.”

The author exclaims, hear it, now we have “material evidence.” What’s wrong with that? The Scriptures aren’t material evidence? Why is there this predisposition to discard the Scriptures themselves as material evidence, hold it in abeyance, and say we’re not going to believe that until we come over here, oh, I can believe that part of the Scripture because over here I’ve got an inscription. Whose authority is it going on? What’s the authority that’s going on here now? We believe the Scripture if and only if it’s “confirmed” (quote) by our human discoveries?

Then it goes on to talk about the problem of silence, and it says there’s so much history, it’s really largely silent about the Exodus, and a lot about the patriarchal evidences. Then on one of the last pages you read this statement, it looks at the evidence of the sea peoples, the evidence of David, and comes forward to the time just at the end of the Old Testament, and it has several references of vocabulary, like Goliath’s spear is called a weaver’s beam, etc. and then it says, “Once again the Bible and archeology are in agreement.”

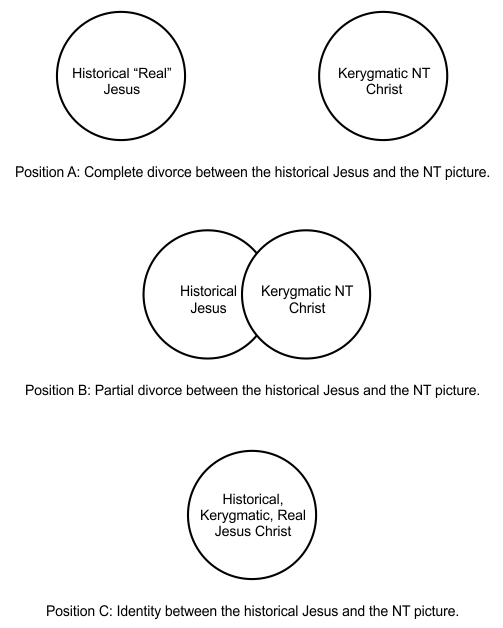

So let’s think about a diagram, if you have the notes on the life of Christ, on page 53 of the notes, you’ll remember that we drew something like this. If you go to any college class today, if you go to any university, the picture of the New Testament that you get looks like this, but you could say it’s true of the Old Testament also:

Figure 2. Three views of the relationship between the “real” historical Jesus and the New Testament picture of Him (the so-called “kerygmatic Christ). Positions A and B show paganized viewpoints whereas Position C shows the biblical worldview. The same three positions could be extended to the entire canon of Scripture.

One of these two pictures, and in the context of tonight in contrast to the page 53 discussion, this will be history and the Bible. Those diagrams are overlapping in one case. The skeptics like to argue that the Person, Jesus Christ of the New Testament, is a product of the church, not a product of history, but Jesus of the Bible or the kerygmatic Christ we called Him, the Lord Jesus Christ’s picture that we get from reading the text of the New Testament is strictly a product cranked out by the people called Christians, that’s their idea of who Jesus was.

But the real Jesus is over here and we don’t really know much about the real Jesus. Yea, we only have four Gospels about Him, but that’s dismissed because we don’t have any “independent” evidence of Jesus. So there’s a split here. The article views history and the Bible overlapping. What did we say, “The Bible and archeology are in agreement.” Whoopee! Now we have a zone where we can be comfortable, this is the comfort zone, and now we can believe because now archeology and the Bible talk about the same thing at the same time in the same place.

If you’re taking notes there are two big points right here. I want to stop and make two principles. The first principle so far is, name one other religion in the world, outside of Judaism, that would even be concerned whether it fits history or not? Can anybody think of one? Confucianism? Do you think Confucianism is critically dependent upon the correlation between Confucius’ writings and Chinese history? Not at all, because Confucius is an ethicist, he just tells you right and wrong. What about Hinduism? Are the content of the Vedas, as modern Hindu accepts them, the religious insights of the Vedas, are these really seriously dependent on Indian history, the history of man? Not really. Isn’t it striking, it’s only the Bible, only the Bible that is even open to discussion about this question. The rest of them would be just like the top circle, history can go on, the Bible is over there, it’s a good story book, hey, want some exciting reading, read the Bible. But I mean, we live in a real world, that’s just make-believe, it’s separated and divorced.

Here the Bible is open to historic criticism. Turn to 1 Corinthians 15, I’ll show you the classic passage. There are other passages in Scripture, the whole Bible is this way, but 1 Corinthians 15 is a rather poignant illustration of this. In 1 Corinthians 15 the topic is what? New Testament, it’s an epistle, Paul is writing, and what is he talking about, in context? The resurrection of Jesus Christ. Is the resurrection of Jesus something historical? Or is it something that occurs in the nth dimension, some sort of spiritual transform? Did it occur in a place in time and history? Yes. Does the Bible insist that it occurs in a time and place of history? Yes it does. So the Bible is open to history.

Look how Paul talks about it, he’s talking, verse 2, “hold fast the word which I preached to you.” Verse 3, “For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, [4] and that He was buried, and that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures,” he’s relating the event to the Scripture. What are the Scriptures he means in verses 3-4? Old Testament. But then what does he do in verses 5-7? Now does he refer to the Scriptures? No he doesn’t. What is he referring to? Eyewitness evidence, historical evidence. So the Bible is written vulnerable to history because it’s God speaking in history. The very fact, I’m trying to struggle to state this first principle, our faith, biblical Christianity, is unique because it’s rooted in a God who speaks into space-time history. That’s a very important point. All the other religions could care less what happens in history. It doesn’t matter. The Bible says that history does matter because that’s the arena in which God spoke.

Another way of stating this first principle: the Bible speaks of God publicly revealing Himself versus God giving thoughts to people’s heads inside, subjective. It’s an objective historic revelation of God. If you were there with a tape recorder or video cassette, and you sat there at the foot of Mount Sinai you would have recorded the words of God speaking in the Hebrew language. You would have heard them. Talk about a best-seller. You could have recorded God speaking in Hebrew. Not English, not Portuguese, at a moment in time the voice of Almighty God boomed into history in the Hebrew language. Amazing! And no other religion claims this.

So the very fact that we’re even debating the historicity of the Scripture is a sign of something very unique about the Bible. It and it alone believes in a contract. Albright, at Johns Hopkins, father of modern archeology, what does he say? After studying all the religions of the world, he says that only the Hebrews made contracts with their God. He got it partially right; actually it was God making contracts with the Hebrews. People always want to know why the Jews are good at business. Well, they’ve been doing business with God for twenty centuries. Talk about people writing contract up, a business contract, they’ve got the original contract right here. And the contract concerns history, that’s why we believe in prophecy. That’s why we believe these things all fit together. Why do men make contracts? Why do you have a contract with the bank? Or I should say when you borrow money why does the bank have a contract with you? To protect the money. And what is the bank going to do if you don’t make payments? They’re going to come after you. What right does the bank have to come after you? Because you broke the contract. So now is the contract relevant to your behavior? You bet it is.

Is this contract, then, relative to God’s behavior in history, and the flow of history? You bet. So right away, the very fact that we’re dealing with archeology and history at all is sort of a left-handed compliment, because it testifies that to come to grips with the Scriptures you’ve got to come to grips with history and if I have to come to grips with history, I know that I live in history and it’s immediately relevant to my life.

The first principle was that biblical faith is a historic faith; it is a public revelation of God. The second principle is that the Bible therefore must be studied in the context of history. Now you see why I’ve been so insistent when we look at Scripture we look at these truths. Notice the diagram again, there’s creation, fall, flood and covenant, and what am I doing with the truths? I’m linking the truths to history, so that what you believe about God, man and nature is determined by this, not your opinion, my opinion or any other person’s opinion, the Bible pegs this to this. If the fall goes away, the whole biblical idea and treatment of evil goes away. If Noah’s flood goes away the picture of God’s judgment/salvation goes away.

You can’t have doctrinal truth without historical integrity; the two go together. My contention has been in Christian circles what we have done, unfortunately and unconsciously, not intentionally, we have raised children through years and years of Sunday School telling Bible stories as though the Bible story is disconnected from Israel’s history, or Egyptian history, or Assyrian history. Then they go to school, they learn about Assyrian history and the Bible is over here. That’s exactly what the secularist wants us Christians to do … that’s exactly what they want us to do, take God out of the classroom, make Him irrelevant, make the whole thing irrelevant, you can believe that, you Christians, we’ll let you believe what you want to believe but this is real. You have your little religious opinions over there but this is structured public knowledge. No, sorry pal, it doesn’t work that way. The Bible makes historic statements.

In the section on the life of Christ, remember, linking again doctrinal truths to history, what did we say about the life of Christ? Remember the virgin birth of Christ was denied because people had an unbiblical view of God, man and nature. Why do people reject the life of Christ? Why do people not like the gospel stories? Why do they insist upon reconstructing a Jesus after their own imaginations, rather than accept the Jesus of the pages of Scripture? Because they have a problem with the idea of revelation, because they cannot come to believe that God speaks and acts, either because they don’t think He’s there or if they do believe, He’s sort of out in the Milky Way somewhere and He doesn’t contact planet earth much.

Now we want to come to some of the questions this article raises. It talks about a catalogue of some findings here and there, but then it’s always punctuated by remarks like this. They go on and say we’re seeing more of the relationship between the Scripture and history. Then they have to deal with cosmology. So after they just got through saying that: “In extraordinary ways, modern archeology has affirmed the historical core of the Old and New Testaments—” this is the historical core of the Scriptures, “corroborating key portions,” portions … portions…portions “of the stories of Israel’s patriarchs, the Exodus, the Davidic monarchy, and the life and times of Jesus. Where it has faced its toughest task has been in primordial history, where many scholars find traces of human origins obscured in theological myth.”

“Ever since Copernicus overturned the church-sanctioned view of Earth as the center of the universe and Charles Darwin posited random mutation and natural selection as the real creators of human life, the biblical view that ‘in the beginning God created the heavens and the Earth’ has found itself on the defensive in modern Western thought. Despite the dominance of Darwin’s theory—that human beings evolved from lower life forms over millions of years—theologians have yielded relatively little ground on what for them is a fundamental doctrine of faith: that the universe is the handiwork of a divine creator who has given humanity a special place in his creation.”

“These apparently conflicting explanations have played a divisive role for centuries. In modern times, the supposed incompatibility of the scientific and religious views of creation have sparked bitter clashes sin the nations courtrooms and classrooms. Often the modern debate has amounted to little more than a shouting match between extremists on both sides,” then they posit a middle-of-the-road position.

Now we’re going to interpret the Bible according to Augustine, that the days of Genesis weren’t really days, they were ages and we can kind of take the evolutionary theory and we can kind of take the Scriptures and put them together. They even quote professors from Christian universities. What have I said? If you want to get unbelief go to a secular university, the tuition is cheaper. They go back to a famous church father, Augustine.

We want to learn a little bit about this because this will be thrown at you if you make it known that you are a fundamentalist, and we have people in our evangelical circles that are ashamed to stand for the Word of God in many areas, so they’ll trot out Augustine. So I want to deal with this because the article, for one whole page says see, now Augustine, he was a pretty good guy, he didn’t get nasty like these fundamentalists. Augustine tried to work science and history together. I mean, after all, he was a peace-maker; we have these divisive fundies all the time. Augustine loved everyone and he brought the world together; he brought the Greeks together with the Christians, he brought neo-Platonism along with biblical Christianity. And he concluded that God had just made the universe in seed form and it later developed by itself, etc.

The problem here is classic. Augustine was very good in some areas. Augustine is looked to … after all, aren’t our Reformed Protestant roots grounded in Augustine? Of course, in soteriology. But Augustine was a disaster in other areas. His eschatology was pathetic. And his idea of creation was awful. Why? Because Augustine was what philosophers call a neo-Platonist, or at least he was influenced by neo-Platonism. And he utilized that, fearful that the Scriptures would not fit into the intellectual climate of the day, he wanted to make the Scriptures fit into this neo-Platonism. The result was he couldn’t believe in a physical literal Kingdom of God yet to come, the Millennial Kingdom.

Why is that? Does anybody know Greek philosophy? What’s the Greek attitude toward material things? They’re bad, so if you’re going to be spiritual, if God’s kingdom is going to be spiritual, it can’t [can’t understand word/s], that people are going to drink wine in God’s kingdom—give me a break; it’s going to be spiritual. So Augustine couldn’t make himself believe all these prophecies about a literal kingdom of God. His neo-Platonism wouldn’t allow that to happen. So here we have a man, a church father, who bought into the world system of thinking, and let the world system of thinking control his theological beliefs. Thankfully, in at least some areas he was inconsistent and the Word of God broke through in his thinking.

What we want to do now is we want to review the basic structure of the empirical approach. The empirical approach is the idea that I can verify something by observation. We’re all taught that in science class, in fact, I use modern science all the time in my work, direct observations, measurements and we devise theories from the measurements, etc. So it’s not like I’m new to this stuff, I do it every day; I have been for 35 years. But as a Christian I have to think through how far I can take the process, how far can I push it, what are the controls on this. As a Christian, as a person who thinks biblically I have to go back to certain observations. Here’s the dilemma of the empirical approach. The person who would approach Scripture and ask whether or not it is true on the basis of observation, be it historical or archeological observation, will only verify a small area of the Bible. He can only verify where these two intersect.

Can you verify the prophesies of the future Kingdom by empirical observation? Can you verify the creation account by empirical observation? Think about that one. If God created the way He created, can you verify it by empirical observation? Think about an easy picture, you’re in the Garden of Eden with your video camera; you are there on the sixth day, you’ve got your video camera set up, you’re an independent observer. I don’t know how the Theophany appears but somehow you see God come and He walks over and He takes the dirt and He builds a body. Whoooo, He blows into it, and there’s a man. If you edited the video tape and gave it to your friend, so you cut out the first part, until Adam appears, then you gave your video tape record of the creation to Joe, and you say Joe, can you tell me how old Adam is? Joe says well, it looks Adam must be 25 or 26 minimum. So you’re telling me that from the start of that video tape backwards has been 26 years? Oh, yea, look at him; he’s a big boy, 26 years old. What has Joe done in this dialogue? He’s used the empirical approach, because every other time he’s looked at a person like that it checks out as 26. The problem is if you get something odd, like creation, resurrections, the Exodus, global floods, axes floating on water, how do you interpret them? Do you interpret them empirically? On what basis?

Let’s go back and look at this and take it apart, because we’re so prone to do this. [blank spot] … but not the way you’d normally see it plotted. This represents intervals over which you can observe. This is five scale intervals, ten to the minus eighteenth of a second, visible light, the sound, one second, one hour, one year, historical period, age of the universe. On that scale what can you observe? What’s the quickest event that you can observe with your eyes? In the winking of an eye, in a fraction of a second, that’s about all you can observe.

Your eyes are very sloppy observers, by the way, because when you go into a movie theater you’re looking at a blank screen most of the time, your brain just thinks you’re looking at a picture, but actually you’re being cheated, you’re paying for a whole picture there which is not on the screen most of the time, it’s just a flash and then the screen goes blank, another flash, screen goes blank, another flash, and your brain says oh gee, look at this nice picture. And it’s been looking at a blank screen most of the night, and you wonder why you get headaches when you go to see it.

Below one second you really can’t see anything, so by direct observation you can’t get to the left of this line. What’s the greatest and longest event that you can witness personally? Your lifetime. So you can’t observe anything beyond here. So that’s the box, the right side of the box is the limit of your lifetime, the left side of the box is the limit of your eyeballs. Let’s look another way. This is a scale of size, ranging down from subatomic particles up to one centimeter, up to the height of a man, up to the height of a mountain, up to the sun, the distance of the sun, the width of the solar system, the galaxies, so there’s spatial. What’s the smallest thing you can see? Probably not quite down to bacteria of the fraction of a centimeter, the smallest thing you can see; as you get older you can’t even see that. Then as you come up the scale you can perceive most of the details of a mountain, if you get far enough away. So it’s kind of fuzzy here. This box is the only place you can directly observe anything. Everyone agree to that?

What we do is we create instruments. We have a microscope; microscopes can see smaller and smaller things. The dentist used to have this neat microscope in his dental office, and you’d sit there, he’d put that probe in your mouth and you could see on TV all the bugs wandering around your mouth. He wanted to convince you that your mouth was the dirtiest part of your body. It always helps when you’re thinking of kissing someone. The microscope is an area where you extend your empirical perception downward. But even a microscope is limited. So you stop down here. With ultra-speed filming you can film high-speed things, we do it at Aberdeen Proving Ground all the time, watching bullets hit armor plates and fracturing all over the place. So you can see that and verify that by cameras. But you’re limited. So similarly a telescope is limited. What’s the point here? The point is empiricism works generally, but not in all cases, and particularly does it not work when you get to the boundaries of this perception level.

Let’s review the four areas where modern thought. They say the Bible is theological myth, we turn that around and say these are empirical myths, what we’re taught in school, basically in cosmology is an empirical myth. What happens is a sleight of hand here; they teach you that the scientific method is great, and they demonstrate it, then they say but science also says this. No, science doesn’t say that, that’s a philosophy that has crept into the scientific vocabulary.

Let’s look at these four things and we want to set forth the principles of the limitations of the empirical approach, or the limitations of man’s knowledge. On the bottom you cannot see down into the atom. A lot of subatomic particle work in physics is mathematical inference. In fact, some physicists are coming to believe that what they’re really dealing with is mathematical debris. In order to make equations balance, you have to introduce terms. You can’t really measure the terms but they have to be there to make the equations work.

So some physicists are coming to the conclusion that maybe what we’re dealing with is just terms in the mathematical equation, just debris. But we can’t tell for sure because we can’t see for sure. So number one, where does this empiricism break down? It breaks down in the subatomic region. We have electrons that spontaneously flip one orbit to the next; no reason why that electron moved and this one didn’t. They can’t figure that out.

What are modern physicists trying to do? They’re trying to say there’s intersecting universes, side by side. You say, what do these guys do, think this up? No, these guys are troubled because if science is going to work it’s got to have a rationality behind it, so if the rationality isn’t available in this universe, that is, we have these chance things that we can’t predict, then they must be caused by something else outside of the universe and we dare not call it the three-lettered word, we can’t utter that one. So we have to say that it must be another universe that intersects with this one and causes these things to happen, anything but G-o-d!

Over here we have ultra-speed filming so you can see a very quick thing, and then you can’t see it anymore. An example of this would be Jesus at the wedding feast. If we had been there with our test tubes and chemical equipment and cameras, and had the ability to film what He did with the water…what is the atomic structure of water? H2O. Are there any carbon atoms in water? What’s wine? What kind of stuff did Jesus do with the electrons and protons in the water? He didn’t drop a sack of Kool-Aid in there. What caused the wine? Carbon atoms were created instantaneously, an amazing thing. And we know enough about chemistry to have an appreciation for what went on there. He blew the minds of the people that tasted the wine, but if we had been there with all of our chemistry, we’d say holy mackerel, how did this happen? Talk about all of a sudden a lot of electrons and protons moved, they sure did, we’ve got carbon atoms now; now we’ve got wine all of a sudden, we’ve got this organic compound that we’ve never had before. Out of H2O we did this. So here’s the Lord Jesus doing these miracles in high speed, down to submicroscopic areas.

The most important thing I want to get to tonight is here. Whenever you speculate about something that happened when human beings weren’t there to visually observe it, you have conjecture. Notice the word, “conjecture.” Everything is conjecture; even creation and theories about the flood are conjecture. We conjecture on the basis of Scripture, but it’s still in the final analysis conjecture of how God did that. The limitations that we’ve said are that all knowledge is limited by our finite capabilities as creatures.

Now for the death blow of all empiricism. Your friend who’s been to university, has their degree, and wants to appear very, very educated, very intellectually impressive, they’ll say I won’t believe in anything unless I see it tested. What they’re doing is they’re saying that all knowledge, watch this now, all knowledge is identical to observe what is observed and if it isn’t observed, it’s not knowledge.

That’s interesting. How do you get to this conclusion? This is a proposition about knowledge. Now follow here; you’re uttering a sentence that says all knowledge is limited to that which is observed, but where did that sentence come from? Did you get that by observation? No you didn’t. That was an assumption that came into the conversation.

So empiricism dies because it can’t justify itself. Empiricism never can justify itself because the doctrine of empiricism isn’t an observed thing. You can’t observe a doctrine; you can’t observe laws of logic; you can’t observe these things, they don’t smell, you can’t measure them as 2.3 centimeters. They’re just ideas; they’re totally immaterial. So empiricism flounders on this crucial foundation that it can’t justify itself; it can’t justify logic, it can’t justify morals, it can’t justify any of the great ideas, including the idea of empiricism. It has always floundered here.

We want to come back to what do we do as Christians? What we do is we raise the question to answer the question. The question when we started tonight was, “Is the Bible True?” What we have done, after we get through all this is we come down and re-ask another question. Is there truth without the Scripture, or is there any Truth (capital T) without the Bible. Can there be Truth without the Bible, because if the Bible isn’t there, God hasn’t spoken, God is not the Creator, then all we have is some chemical phenomenon in our brains, but that’s not Truth, that’s just chemical phenomenon.

So if we’re going to claim there’s Truth, we have to have something to base that on, and we as Christians come back to the fact that we think God’s thoughts, we don’t try to generate, we don’t try to think like God independently of God. We think God’s thoughts after Him, so our thoughts are derivative of His thoughts. We believe in Truth, but we believe that Truth is God’s Truth first and ours secondarily, and that when it comes to ethics, laws of logic, and the concepts and ideas, they are basically there because God created them. And beginning with the creation and beginning with the authority of the Word of God, then we go forth and we wind up where we started tonight. Let’s go back to Genesis 2.

Now we come to the true way we should observe things, where God commissioned us to observe things. In the garden God fashioned a man, and verse 19 He gives tremendous empirical authority to man, to you, me, to the whole human race. “And out of the ground the LORD God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the sky, and brought them to the man” look at this purpose clause, why did God bring them to man, “to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called a living creature, that was its name.” What delegated authority that is! God is delegating to us as people created in His image the right to go out and study empirically the creation around us and name it, meaning to understand it. That’s a mandate, that’s a divine mandate.

There’s the basis for science in Scripture, but it’s only after… what has taken place before Genesis 2:19? Adam was to name the creatures brought forth to Him, but who named light “light?” Was that Adam or was that God? Who named the sea and the earth? Was that Adam or was that God? In other words, you’ve heard the expression priming the pump; God primed the language machine. God primed knowledge, then He turns it over to us and says creature, I’ve created this for you, you have a function in this creation that I have made, and I tell you that you are to go out and study this creation, and you are to name it, you are to conquer it, you are to come to conclusions on an empirical basis, but you’re going to do so because first you start with the Word of God. In every area you start with the Word of God, and then you move out, whether it’s finances, whether it’s business, whatever, you always start with the Word of God and move from there.

Going back to Adam and Eve, the proper place is to listen to what He says, and then go out. Why do you suppose, in another little imaginative exercise, why do you suppose God wants us to go out and name animals? Just because He’s interested in a zoological book that we can create? He knows the animals. Why do you suppose He has us do that? Why do you suppose He commissions man to go out and observe and draw conclusions? What are we drawing conclusions about as we draw conclusions about the animals? We’re drawing conclusions about what? The Maker of the animals.

Therefore, biblical observation and science in empirical approach is a form … now this will blow some of your minds, it’s a form of worship. It is a form of worship! If you have a hard time connecting your area of specialty, be it whatever, some interest, some hobby of yours, you really haven’t got it together scripturally until you can go forward in that hobby or that profession and rejoice in God each day, because you’re seeing the stuff that you’re manipulating. It can be data for people, it can be whatever, but you’re manipulating, you’re working, you’re doing, you’re out there naming names and that is an act of worship as a Christian walking by faith in your Father’s creation, in His neighborhood.

Question asked: Clough replies: The question is what about Islam, aren’t they linked to history. Yes they are, but they’re linked to history only because of their biblical background. Islam is kind of an aping of Judeo-Christianity; it’s kind of a perverted version. But yes, it’s related to history. I don’t know whether you noticed in the news this week that the [not sure of word] in Great Britain have sentenced to death one of the English playwrights for writing a sacrilegious play about Jesus, and why are they worried about a sacrilegious play against Jesus? Because in Islam Jesus is a prophet, He’s a prophet of Allah. So to write this demeaning play, any Islamic nation with a duly instituted judicial system under Islamic law has a right to kill this playwright if he ever sets foot in any of their countries, because he has blasphemed.

That’s an interesting defender of Jesus, but in any case, Islam has a historical thing. Mainly they weaken it because in Islam the Koran is the final authority, and they allow errors in the rest of the Bible, because now they’re rooted in the Koran to go backwards and the Koran can verify the Scriptures. So they could be tolerant of errors in the Bible. In practice your Islamic fundamentalists, I’m told, in Islamic countries have the same problem in Christian countries, namely that they have all these Islamic governments, you hear about the terrorists and this and that, those guys are no more representative of mainstream Islam than the most radical anti-Semitic (quote) “Christian” militia group would be related to Christianity. A lot of the Islamic countries are run by liberal Islamism, they give lip service. Saddam Hussein is a good example, he could care less about Islam. He just uses it like in our culture politicians use Christianity. So you have to kind of keep that in mind when you hear these guys spout off. They’re spouting off for the home choir is what they’re doing, they could personally care less about Islam.

Islam is suffering much from within itself from liberalism. The academic Muslim scholars no longer believe a literal Genesis. In Turkey and some of the other countries our creationists have gone and given conferences to the fundamentalists Islamics because they’re upset about their own liberals. So it’s kind of a convoluted thing that’s going on there in Islam.

Question asked: Clough replies: But the reason that happens, the way the college professors will do this in the class, and it really screws the students up, they’ll say to get the students thinking this way they’ll say well, you’ve played the game, you take a note, or you tell a string of people and you tell a story to this person and they tell it to the next person and they tell it to the next person, and by the time it comes around the room it’s totally screwed up. So they’ll do that empirical demonstration and they’ll say see, you can’t have oral tradition or written tradition or anything else transmitted without it getting fouled up, so how can you sit here as Christians and claim the Scriptures were preserved.

The answer is because we don’t treat the Scriptures as though they’re just another human message. It’s all convoluted. That’s the very question at hand, is the Scripture the Word of God or isn’t it. If it is the Word of God, then there’s a reason, a rationale of why it’s inerrant. But the argument against inerrancy of Scripture is all founded on the presupposition that the Scriptures are of man. Then having made that grand announcement we treat it just like any other document, Shakespeare, Plato or somebody else, and we say see, there are transmission problems there, etc. so there has to be in the Bible. But that’s circular reasoning, because the whole discussion in the first place was is the Bible to be categorized in the same genre as Shakespeare and as these other documents. That’s the whole point.

That’s what Adam and Eve did. This gets back to that same thing. Satan’s proposition and God’s proposition are set on an equal plain and then man comes along and decides which is right. The error is right here, it’s not the Creator/creature distinction. It’s being erased at step one in the discussion. I’ve been fouled up so many times myself in discussing this question of not getting the first step right. And sometimes I get sidetracked, so you just have to think this through because Satan takes us all for a ride all the time. We don’t notice we’re getting deflected and the first thing, now we’re out in the toolies somewhere, or worse when we’re trying to share the gospel with somebody, it’s how the heck did we get out here. You feel frustrated yourself for winding up out here. Wait a minute, this isn’t right, and if you trace it back you’ll see that somewhere at the beginning is where the mistake occurred.

Let me give an example. I listened to a tape with a fellow who was discussing with a so-called Christian homosexual the issue of gay rights. I don’t like to use the word “gay,” I think I’ll start using the word “sodomite.” It’s a good biblical word and it’s in the dictionary, so it’s not a hate term. Look at Webster’s Dictionary, blow the dust off of it and open it up once in a while. He was on the radio and the homosexuals, on this talk show, there were two of them, and they said well, the evangelicals are so hateful, they just hate us, and they’re very seriously dangerous people because they’re promoting these hate crimes, never mention the fact that at least 10-15 Christian kids have been shot in the last year of so, we don’t mention that, those aren’t hate crimes.

So they were going on and on that the essence of Christianity is love, and grace, and acceptance of people, and here you have these sticks-in-the-mud, fundamentalists, nasty people, bitter-spirited, mean-spirited, and always knocking us homosexuals, making us feel like we’re second class citizens, blah, blah, blah. Some of it, frankly, may be true, maybe instead of making the issue what we should we’re not, but that’s independent. This shrewd Christian, I was intrigued because the whole discussion has been set up the first three or four minutes of the talk show. So now they turn to this guy, thinking they’re going to put him on the spot. Well, he had a wonderful step one. He just said well, what is the issue here? So the first thing he did was he didn’t buy into what the sweep was, he wasn’t defending whether we’re loving or mean-spirited. That’s what they wanted him to do, they wanted to maneuver him to continue the frame of reference that had already been set in motion in the first three or four minutes of the talk show.

What he did he just stopped cold, and he said, excuse me, but the issue here is the terms and rights (these were Christians in a Christian church.) He said, it’s the definition of Christian membership. He said if I were a believer in the free market economy I wouldn’t be accepted in the communist party. It has nothing to do with my personality whether the communists hate me or don’t hate me, it’s just simply the terms of joining the Marxist view of economics is that you give up your view of the free enterprise system. So this is not discriminating against you as a person, it’s just simply what is the standard of membership, and the standard of membership in the Christian church is the Bible. With that, now where’s the discussion going? Well, what does the Bible say? It was just a shrewd move. Would to God that we could all be that skillful in that situation. But it was wonderful because he moved the discussion over to where it should be.

Now they’re trying to explain their way, oh Romans 1 and Leviticus and for the next five minutes they were all over the rug, and it was great to listen to because he moved the discussion over to his ground. I don’t think our evangelism does that a lot. When we get into the death of Christ, that’s something as I’ve gone through these notes and generated the notes, someone asked four or five weeks ago about animal sacrifice and that’s what we’ve been covering the last two times, you’ll see it in the notes, and as I went through that the thought came to me, you know, years ago in this country when liberalism was in its coming out period of the 20s they used to attack us, the fundamentalists, they used to attack us by saying you people have a bloody, gory religion. You just can’t, in the 20th century, we’ve evolved higher than that, we no longer worry about bloody religion, you know, we’ve got an advanced civilization here, we’re going to talk about ethics and Jesus and man, and what He can do for us and blah, blah, blah.

This event that we’re studying in the life of Jesus is the Cross. The set of notes that just came out tonight, read in there what do the liberals have to do with the Cross? Now you’ve got a problem. See, it’s a litmus test. Whatever one does to the Cross of Jesus Christ exposes their theology, because the only people that get it right are the people that are looking for a blood atonement to atone for their sins before a holy God. If you’re not coming to the Cross of Jesus Christ with that in mind, what you come out with is, “Oh, gee that was a tragedy of history. Jesus was noble, He died for His cause and that gives me great inspiration.” There were a lot of other martyrs that died, during Vietnam they had Buddhist monks pouring gasoline on themselves and frying themselves in the street. So hey, there have been other martyrs, but that’s what the cross has to be reduced to in a bloodless religion. It’s just an example, inspiring? Yeah, it’s inspiring, but that’s all the Cross is, is an inspiration, whereas for us it accomplished something, there was a transaction going on at the Cross. Watch that, it’s come out as we’ve gone through these notes.

But you don’t hear that anymore, and do you know why I think we don’t hear it anymore? Because even in our evangelical circles the gospel has become seriously compromised. The gospel message comes across as though it’s a psychological pill, accept Jesus because He’ll straighten out your life. Accept Jesus because He’ll make you feel better, do you feel depressed, accept Jesus.

Some of those things are true, but the problem is that’s not the gospel. The gospel isn’t a subjective psychological thing, it’s a judicial transaction thing. That never rings a bell, so if someone comes to the gospel thinking of it as a psychological thing, do you see the seriousness of that? It means they have never come to grips with sin. Which means they have never come to grips with the holiness of God, which means they have never come to grips with Who God is. So you leave out God and sin, God, holiness, and sin, and of course you get it wrong. This is why I keep on insisting that you’ve got to back through the order of Scripture. It takes time. Yes it takes time, but in a pagan society like we live in we can no longer assume that “Joe on the street” has enough (quote) “Scripture” floating around in the back of his head that he picked up in a bar somewhere and that he’s got it basically right so all I have to do is just add a few things about accepting Jesus into your heart. No! I don’t think so. The average “Joe on the street” doesn’t have a clue what’s going on.

Unlike fifty years ago, our parent’s generation, we can no longer witness the way they witnessed because the society is downgraded so far we’ve got to go back, fortunately we’ve got a model, the whole book of Acts. Paul sent out into a society more pagan than ours, much more pagan than ours. So we have to study how did the apostles preach Christ? That’s why the quote is in the first part of this chapter from Leon Morris’s book, The Cross of Christ. What does Leon say? He says that the central theme in the whole New Testament is the Cross, Jesus never asked anybody to remember His birthday but He did ask people to remember His death. That’s the center of the gospel. So what we’re coming to is the gospel, and when we come to the cross we’re going to see the aberrant, stupid, foolish sub-biblical ideas of the Cross of Jesus. It’s a sad commentary on our times.

Question asked: Clough replies: That’s a good point; I had that in my notes. One of the friendly things about the article, actually two things, at least the article has a concept of truth. The problem is they haven’t got it justified and located correctly. They’re not approaching it saying well gee, if the Bible gives you kicks and if that’s your thing and it turns you on well, read the Bible. That would be a real contemporary idea of the Scriptures, read it because it turns you on. At least they’re asking is it true or false? So that’s one good thing. The other good thing about it is that at least they recognize that the Bible contacts history, and that what goes on in history is relevant to the Scriptures. So God bless for that, because a lot of the liberal critics dismiss the whole historicity of Scripture, could care less about it.

Question asked: Clough replies: What has happened, when you get away from the authority of Scripture, you do a similar thing that the Roman Catholic Church did, you inject a priesthood in between the Scriptures and people, before it was the old Catholic priesthood, but in this case who are the priests? The scholars, so now everybody has to sit in hushed tones to listen to the latest erudite report from the scholars, because all the rest of us are too stupid to understand the Scripture, we have to wait, and the church, my goodness, the church has waited nineteen centuries for all this light. What did they do for the last nineteen centuries? Poor apostle Paul, he just didn’t have all this extra archeology.

Question asked: Clough replies: The article made it appear like this was a sudden new thing in archeology, and it really isn’t suddenly new, it’s probably new to the author, but it hasn’t been new.

Our time is up.

U.S. NEWS & WORLD REPORT OCTOBER 25, 1999

IS THE BIBLE TRUE?

Extraordinary insights from archaeology and history

The workday was nearly over for the team of archaeologists excavating the ruins of the ancient Israelite city of Dan in upper Galilee. Led by Avraham Biran of Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem, the group had been toiling since early morning, sifting debris in a stone-paved plaza outside what had been the city’s main gate. Now the fierce afternoon sun was turning the stoneworks into a reflective oven. Gila Cook, the team’s surveyor, was about to take a break when something caught her eye—an unusual shadow in a portion of recently exposed wall along the east side of the plaza. Moving closer, she discovered a flattened basalt stone protruding from the ground with what appeared to be Aramaic letters etched into its smooth surface.

She called Biran over for a look. As the veteran archaeologist knelt to examine the stone, his eyes widened. “Oh, my God!” he exclaimed. “We have an inscription!” In an instant, Biran knew that they had stumbled upon a rare treasure. The basalt stone was quickly identified as part of a shattered monument, or stele, from the 9th century B.C., apparently commemorating a military victory of the king of Damascus over two ancient enemies. One foe the fragment identified as the “king of Israel.” The other was “the House of David.”

The reference to David was a historical bombshell. Never before had the familiar name of Judah’s ancient warrior king, a central figure of the Hebrew Bible and, according to Christian Scripture, an ancestor of Jesus, been found in the records of antiquity outside the pages of the Bible. Skeptics had long seized upon that fact to argue that David was a mere legend, invented by Hebrew scribes during or shortly after Israel’s Babylonian exile, roughly 500 years before the birth of Christ. Now, at last, there was material evidence: an inscription written not by Hebrew scribes but by an enemy of the Israelites a little more than a century after David’s presumptive lifetime. It seemed to be a clear corroboration of the existence of King David’s dynasty and, by implication, of David himself.

Beyond its impact on the question of David’s existence, however, the discovery provided a dramatic illustration of the promise and peril that come into play whenever the Bible is weighed on the scales of modern archaeology. In one moment, the unearthing of an inscription or artifact can shed new light or cast a shadow on a passage of Scripture and in the process shatter the presuppositions of biblical scholarship. One kind of truth is confirmed or replaced by another. In extraordinary ways, modern archaeology has affirmed the historical core of the Old and New Testaments—corroborating key portions of the stories of Israel’s patriarchs, the Exodus, the Davidic monarchy, and the life and times of Jesus. Where it has faced its toughest task has been in primordial history, where many scholars find the traces of human origins obscured in theological myth.

IN THE BEGINNING

Ever since Copernicus overturned the church-sanctioned view of Earth as the center of the universe and Charles Darwin posited random mutation and natural selection as the real creators of human life, the biblical view that “in the beginning God created the heavens and the Earth” has found itself on the defensive in modern Western thought. Despite the dominance of Darwin’s theory—that human beings evolved from lower life forms over millions of years—theologians have yielded relatively little ground on what for them is a fundamental doctrine of faith: that the universe is the handiwork of a divine creator who has given humanity a special place in his creation.

These apparently conflicting explanations have played a divisive role for centuries. In modern times, the supposed incompatibility of the scientific and religious views of creation have sparked bitter clashes in the nation’s courtrooms and classrooms. Often the modern debate has amounted to little more than a shouting match between extremists on both sides—fundamentalists, who dismiss evolution as a satanic deception, and atheistic naturalists, who assert that science offers the only window on reality and who seek to discredit religious belief as ignorant superstition.

Listening to some of the rhetoric today, one might easily assume that the views espoused by creationists—that God created the universe in six 24-hour days, as a literal reading of Genesis 1 would suggest—represent the historic position of Christianity and of the Bible, and that it is only in modern times, with the rise of evolutionary theory, that creationism has come under siege. Yet this is hardly the case.

As early as the 5th century, the great Christian theologian Augustine warned against taking the six days of Genesis literally. Writing on The Literal Meaning of Genesis, Augustine argued that the days of creation were not successive, ordinary days—the sun, after all, according to Genesis, was not created until the fourth “day”—and had nothing to do with time. Rather, Augustine argued, God “made all things together, disposing them in an order based not on intervals of time but on causal connections.” Sounding like an evolutionist, Augustine reasoned that some things were made in fully developed form and others were made in “potential form” that developed over time to the condition in which they are seen today.

Now, a growing number of conservative scholars embrace theistic evolution—a view that considers evolution, like all other physical processes known to science, to be divinely designed and governed. They understand Genesis as speaking more of the relationship between God and creation than as presenting a scientific or historical explanation of how and when creation occurred. “Creation and evolution are not contradictory,” explains Howard Van Till, a professor of physics and astronomy at evangelical Calvin College in Grand Rapids, Mich. “They provide different answers to a different set of questions.”

Much the same may be said of disputes over the meaning and intent of the biblical story of the Flood. Those who take it as literal history believe that God unleashed a worldwide deluge that destroyed all air-breathing life on Earth except for those creatures taken aboard the ark in divine judgment against a creation gone bad. When God finally allowed the waters to recede, the ark was emptied and the world was repopulated by the creatures that disembarked. Based on biblical genealogies, all of this would have happened less than 10,000 years ago.

While most biblical scholars consider the story of the Flood a myth, many conservatives have little difficulty imagining that God could pull off precisely what the Genesis story describes. As with the Creation narrative, however, the evidence and arguments from science stack up overwhelmingly against a literal interpretation of the Flood story. Where, for example, would such a volume of water have come from, and where would it have gone afterward? How would mammalian life have re-emerged on isolated islands and landmasses that emerged from the receding flood waters? While some scholars allow the possibility that a catastrophic regional deluge may underlie the flood legends of the ancient Near East, conservatives argue that there is, indeed, geological evidence consistent with a universal deluge. But such arguments have found little support within the scientific mainstream.

AGE OF THE PATRIARCHS

The book of Genesis traces Israel’s ancestry to Abraham, a monotheistic nomad who God promises will be “ancestor of a multitude of nations” and whose children will inherit the land of Canaan as “a perpetual holding.” God’s promise and Israel’s ethnic identity are passed from generation to generation—from Abraham to Isaac to Jacob. Then Jacob and his sons—the progenitors of Israel’s 12 ancient tribes—are forced by famine to leave Canaan and migrate to Egypt, where the Israelite people emerge over a period of some 400 years.

Modern archaeology has found no direct evidence from the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1500 B.C.)—roughly the period many scholars believe to be the patriarchal era—to corroborate the biblical account. No inscriptions or artifacts relating to Israel’s first biblical ancestors have been recovered. Nor are there references in other ancient records to the early battles and conflicts reported in Genesis.

Moreover, some scholars contend that the patriarch stories contain anachronisms that suggest they were written many centuries after the events they portray. Abraham, for example, is described in the 11th and 15th chapters of Genesis as coming from “Ur of the Chaldeans”—a city in southern Mesopotamia, or modern-day Iraq. But the Chaldeans settled in that area “not earlier than the 9th or 8 th centuries” B.C., according to Niels Peter Lemche, a professor at the University of Copenhagen and a leading biblical skeptic. That, he says, is more than 1,000 years after Abraham’s time and at least 400 years after the time of Moses, who tradition says wrote the book of Genesis.

Yet other scholars, like Barry Beitzel, professor of Old Testament and Semitic languages at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School in Deerfield, Ill., are neither surprised nor troubled by the apparent lack of direct archaeological evidence for Abraham’s existence. Why, they argue, should one expect to find the names of an obscure nomad and his descendants in the official archives of the rulers of Mesopotamia? These are “family stories,” says Beitzel, not geopolitical history of the type one might expect to find preserved in the annals of kings.

While there may, indeed, be no direct material evidence relating to the biblical patriarchs, archaeology has not been altogether silent on the subject. Kenneth A. Kitchen, an Egyptologist now retired from the University of Liverpool in England, argues that archaeology and the Bible “match remarkably well” in depicting the historical context of the patriarch narratives.

In Genesis 37:28, for example, Joseph, a son of Jacob, is sold by his brothers into slavery for 20 silver shekels. That, notes Kitchen, matches precisely the going price of slaves in the region during the 19th and 18th centuries B.C., as affirmed by documents recovered from the region that is now modern Syria. By the 8th century B.C., the price of slaves, as attested in ancient Assyrian records, had risen steadily to 50 or 60 shekels, and to 90 to 120 shekels during the Persian Empire in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. If the story of Joseph had been dreamed up by a Jewish scribe in the 6th century, as some skeptics have suggested, argues Kitchen, “why isn’t the price in Exodus also 90 to 100 shekels? It’s more reasonable to assume that the biblical data reflect reality.”

FLIGHT FROM EGYPT

The dramatic story of the Exodus—of God delivering Moses and the Israelite people from Egyptian bondage and leading them to the Promised Land of Canaan—has been called the “central proclamation of the Hebrew Bible.” Yet archaeologists have found no direct evidence to corroborate the biblical story. Inscriptions from ancient Egypt contain no mention of Hebrew slaves, of the plagues that the Bible says preceded their release, or of the destruction of the pharaoh’s army during the Israelites’ miraculous crossing of the Red Sea. No physical trace has been found of the Israelites’ 40-year nomadic sojourn in the Sinai wilderness. There is not even any indication, outside of the Bible, that Moses existed.

Still, as with the patriarch narratives, many scholars argue that a lack of direct evidence is insufficient reason to deny that the Exodus actually happened. Nahum Sarna, professor emeritus of biblical studies at Brandeis University, argues that the Exodus story—tracing, as it does, a nation’s origins to slavery and oppression—“cannot possibly be fictional. No nation would be likely to invent for itself . . . an inglorious and inconvenient tradition of this nature,” unless it had an authentic core. “If you’re making up history,” adds Richard Elliott Friedman, professor at the University of California-San Diego, “it’s that you were descended from gods or kings, not from slaves.”

Indeed, the absence of direct material evidence of an Israelite sojourn in Egypt is not as surprising, or as damaging to the Bible’s credibility, as it first might seem. What type of material evidence, after all, would one expect to find that could corroborate the biblical story? “Slaves, serfs, and nomads leave few traces in the archaeological record,” notes University of Arizona archaeologist William Dever.

The dating of the Exodus also has long been a source of controversy. The book of 1 Kings 6:1 gives what appears to be a clear historical marker for the end of the Israelite sojourn in Egypt: “In the 480th year after the Israelites came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, he began to build the house of the Lord.” Biblical historians generally agree that Solomon, the son and successor of David, came to the throne in about 962 B.C. If so, then the Exodus would have occurred in about 1438 B.C., based on the chronology of the 1 Kings passage.

That date does not fit with other biblical texts or with what is known of ancient Egyptian history. But the flaw is far from fatal. Sarna and others argue that the time span cited in 1 Kings—480 years—should not be taken literally. “It is 12 generations of 40 years each,” notes Sarna; 40 being “a rather conventional figure in the Bible,” frequently used to connote a long period of time. Viewing the 1 Kings chronology in that light—as primarily a theological statement rather than as “pure” history in the modern sense—the Exodus can be placed in the 13th century, in the days of Ramses II, where it finds strong circumstantial support in the archaeological record.

THE RULE OF DAVID

The reigns of King David and his son Solomon over a united monarchy mark the glory years of ancient Israel. That period (roughly 1000 B.C. to 920 B.C.)—described in detail in the books of 1 and 2 Samuel, 1 and 2 Kings, and 1 and 2 Chronicles—marks the beginning of an era of stronger links between biblical history and modern archaeological evidence. Before the discovery of the “House of David” inscription at Dan in 1993, it had become fashionable in some academic circles to dismiss the David stories as an invention of priestly propagandists who were trying to dignify Israel’s past after the Babylonian exile. But as Tel Aviv University archaeologist Israel Finkelstein observes, “biblical nihilism collapsed overnight with the discovery of the David inscription.”

In the aftermath, another famous ancient inscription found more than a century ago has attracted renewed scholarly interest. The so-called Mesha Stele, like the stele on which the Dan inscription is etched, is a basalt monument from the 9th century B.C. that commemorates a military victory over Israel—this one by the Moabite king Mesha. The lengthy Tyrian text describes how the kingdom of Moab, a land east of the Jordan River, had been oppressed by “Omri, king of Israel” (whose reign is summarized in 1 Kings 16:21–27) and by Omri’s successors, and how Mesha threw off the Israelites in a glorious military campaign.

But the name of another of Mesha’s conquered foes may lie hidden in a partially obliterated line of text that, transliterated, reads b[ñ]wd; the remainder of the inscription is missing. The French scholar André LeMaire, after carefully re-examining the inscription, has suggested that the line should be filled in to read bt dwd—“beit David,” or “house of David”—a reference to the kingdom of Judah. “No doubt,” says LeMaire, “the missing part of the inscription described how Mesha also threw off the yoke of Judah and conquered the territory southeast of the Dead Sea controlled by the House of David.”

As significant as they are, these two inscriptions—both still contested—remain for now the only extra biblical references to David’s dynasty. And both were written more than a century after the reigns of David and Solomon. Given the grandeur of the Israelite monarchy under the two kings as described in the Bible, how could such an influential and popular regime have attracted so little notice in ancient Near Eastern documents from the time?

The answer, suggests Carol Meyers, professor of biblical studies and archaeology at Duke University, may lie in the political climate in the region at the time, when, she says, “a power vacuum existed in the eastern Mediterranean.” The collapse of Egypt’s 20th dynasty around 1069 B.C. led to a lengthy period of economic and political decline for a nation that had exerted powerful influence over the city-states of Palestine during the Late Bronze Age. This period of Egyptian weakness, which lasted for over a century (until around 945 B.C.), saw a “relative paucity of monumental inscriptions,” says Meyers. “The kings had nothing to boast about.”

Similarly, the Assyrian empire to the east was unusually silent from the late 11th to the early 9th century B.C. regarding the western lands it once had dominated. Assyria was preoccupied, says Meyers, with internal turmoil following the death of one of the greatest of its early kings. Another major power in the region, Babylonia, also was uncharacteristically quiet. For centuries following a raid on Assyria in 1081 B.C., it seldom ventured beyond its own borders, says Meyers, “and thus its records would hardly have mentioned a new dynastic state to the west.”